Editor’s note: This article is republished as it appears in The Conversation, an independent news publisher that works with academics worldwide to disseminate research-based articles and commentary. The University of Oregon partners with The Conversation to bring the expertise and views of its faculty members to a wide audience. For more information, see the note following this story.

The new Supreme Court term begins on the first Monday in October, a date set more than 100 years ago by Congress. As expected, the court’s upcoming docket will include some politically controversial cases, as did the term that ended in June. Less expected, that previous term featured some notable liberal victories in cases about immigration, homosexuality and abortion.

Nevertheless, the last Supreme Court term was far from a liberal triumph, and for several reasons.

First, as commentators have noted, the term also saw many conservative decisions. And as one court observer has argued, the liberal decisions were made on narrow legal grounds, with limited scope and future applicability, whereas the conservative ones were broader.

As a scholar who specializes in the Constitution and the courts, I see another reason why the last term was not a liberal triumph and why the Roberts court remains a bastion of conservatism: the types of decisions that the court made.

Simply put, some Supreme Court decisions are enduring, while others are fleeting and easily changed.

Different kinds of decisions

The Supreme Court decisions that have the greatest impact on our governments and our laws are rulings that find violations of the Constitution, called “constitutional invalidations.”

When the court declares that some government action – a law or an executive order – is unconstitutional, that action must stop. Neither Congress nor the states can do anything to change this result, except through a constitutional amendment, which is almost impossible to attain because it requires two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress, plus the consent of three-quarters of the states.

But most Supreme Court decisions do not declare constitutional violations. Most decisions either reject claims of constitutional violations or else engage in statutory, as opposed to constitutional, interpretation; that is, they simply determine what a federal law requires in cases where that question is legally contested.

Unlike constitutional invalidations, the consequences of these other decisions are relatively easy to change.

First, the government can always stop doing what it has been doing, even if the court declared it has been acting constitutionally. And second, Congress can always amend or repeal the laws it has passed if it disagrees with the court’s interpretation of these laws.

The distinction between constitutional invalidations and other decisions therefore marks the difference between the most consequential exercises of Supreme Court power and decisions that are far less significant because they are more amenable to change by the other branches of government.

The liberal decisions

This difference shows why the recent Supreme Court term was far from a liberal triumph.

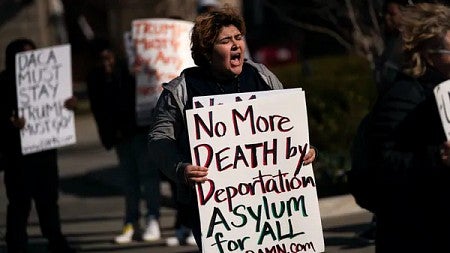

Two of the three principal decisions touted as liberal victories are the reinstatement of DACA, a program allowing people brought to the U.S. illegally as children to avoid deportation that the Trump administration revoked in 2017, and the prohibition on employment discrimination against homosexuals or transgender individuals. The decisions in both cases involved statutory interpretations, meaning they can be easily overriden.

The DACA decision rejected the claim that the government’s revocation of DACA violated the Constitution, ruling only that the revocation was carried out in a an arbitrary and capricious manner that violated a federal statute.

Either Congress or the Trump administration could therefore end DACA, the administration simply by following different, less arbitrary procedures. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh put it, “(T)he only practical consequence of the court’s decision … appears to be some delay.”

The decision providing protection from employment discrimination for gay and transgender people was also based on statutory interpretation. The justices found that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided remedies against such discrimination. Congress could therefore remove these protections by amending the Civil Rights Act, though it seems unlikely to do so.

The third ruling celebrated by Democrats, striking down a Louisiana statute that threatened to leave the state with a single abortion clinic, actually did find a constitutional violation. This 5-4 decision is therefore not subjected to legislative override.

On closer look, however, the case may actually undermine constitutional protections for abortion. The decision was based on a recent precedent which invalidated a similar statute from Texas merely four years earlier. But Chief Justice Roberts, who cast the fifth and crucial vote in last term’s case, made clear he was willing to weaken that precedent in the future.

The conservative decisions

By contrast, the three big conservative victories from the court’s last term involved two groundbreaking constitutional invalidations.

One constitutional invalidation weakened the independence of federal administrative agencies, a longstanding conservative ambition. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which was established in 2010 to protect American consumers in the financial markets, violated the Constitution.

The decision made that agency, and theoretically others like it, more vulnerable to political pressure from the White House.

In a second major 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional for states seeking the separation of church and state to refuse government scholarships to pupils of private religious schools. This is a big victory for the religious right, which has long sought public funding for religious institutions.

Since these are constitutional invalidations, nothing short of a constitutional amendment, or a future change of heart at the Supreme Court, can undo these two decisions.

The decision was not only a big practical win for the Trump administration, which has made the crackdown on asylum seekers one of its main policies. It also deprived liberals of what had been a significant migrant rights victory at the lower court, significant because it came in the form of a constitutional invalidation, which the Supreme Court has now reversed.

A staunchly conservative court

In short, when evaluating the court’s performance, it is crucial to distinguish between different types of decisions. The most formidable and enduring are those that find constitutional violations.

That is why the Roberts court is so staunchly conservative. In pivotal areas, from the right to bear arms and campaign finance to affirmative action and religious freedom, conservative victories often come in the form of enduring constitutional invalidations.

Meanwhile, important liberal decisions are often easy to circumvent and unlikely to last.![]()

—By Ofer Raban, School of Law