Editor’s note: This article is republished as it appears in The Conversation, an independent news publisher that works with academics worldwide to disseminate research-based articles and commentary. The University of Oregon partners with The Conversation to bring the expertise and views of its faculty members to a wide audience. For more information, see the note following this story.

Oregon voters have long cast their ballots by mail in many types of elections, including for local, state and federal offices. They started doing so in 1987 and have voted exclusively by mail in all elections since 1998.

For much of that time, I and others have studied how mail-in voting affects voter turnout, as well as the potential for partisan advantage or voter fraud.

Oregon’s experience shows that mail-in voting can be safe and secure, providing accurate and reliable results the public can be confident in. As more voters consider using mail-in voting than ever before, there are some lessons they, and their local and state election officials, can learn from Oregon, to help things move more smoothly.

Consider timing

Not everyone in the U.S. knows how to vote by mail. They’ll need help from state and local officials so they know what to do. Ideally this will start early, with instructions about how to get a mail-in ballot in advance of the actual ballots being sent out to voters.

In Oregon, all registered voters are automatically sent a ballot about three weeks before Election Day. This gives people plenty of time to receive their ballots, consider the options and mark and return the ballots.

By accepting mail-in ballots in September or early October, states would get a good sense of how many people will be voting by mail. That would also give election officials and the postal system time to make plans to handle the additional traffic.

Teach voters what’s expected

In any state, when a voter receives the ballot, they must mark it, making their selections for candidates and their choices on referenda or other ballot questions.

In Oregon, after marking the ballot, the voter puts it into what’s called a “ballot secrecy envelope,” which contains no identifying information. This prevents election workers or others from knowing which person cast the ballot inside.

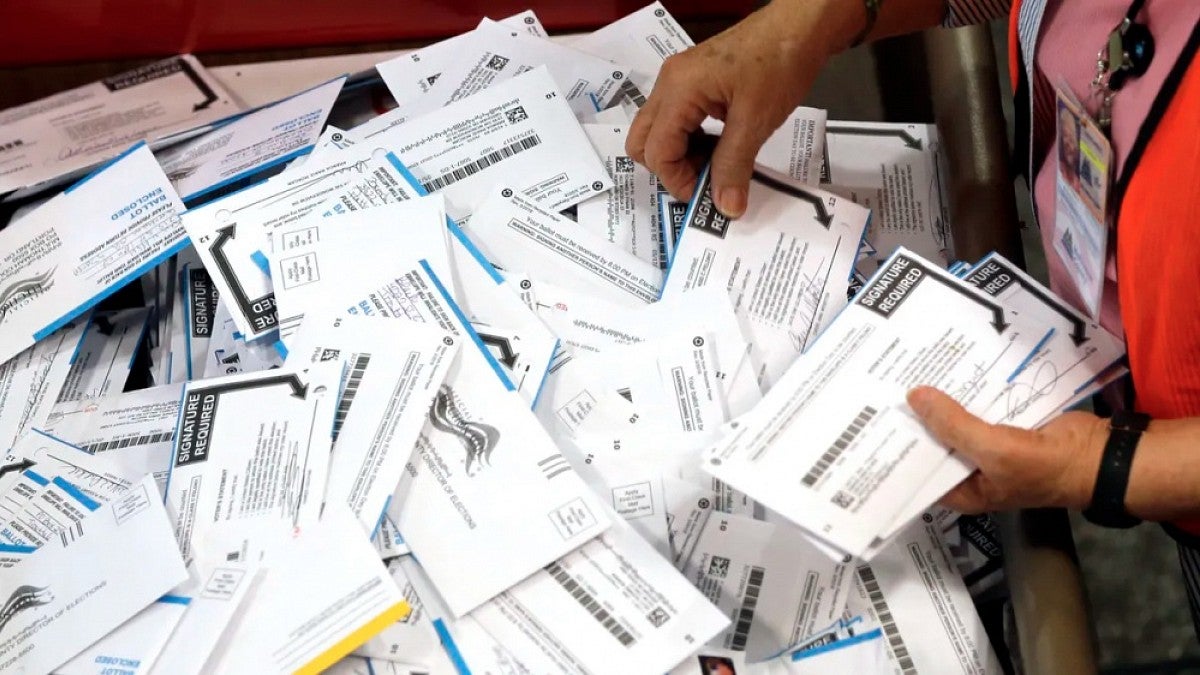

That secrecy envelope goes into a second envelope, which is what is delivered to election officials. Each voter must sign the outside of that second envelope. Then the voter can mail the ballot back to their local election office; in some places, postage is already paid, but in others voters need to put one or more stamps on it. Alternately, the voter can take the second envelope with its contents to one of several drop-off boxes set up around each community in the state. Many states are planning to set these up and have them regularly monitored by election officials, who collect the ballots.

When the ballots arrive at the local election office, the name and signature on the envelope are compared to the official registration records. If the signatures don’t match, the voter is notified by mail, and given the opportunity to correct or explain the discrepancy. Of course, such corrections take time, so this is a good reason for voters who are casting their ballots by mail to send in their votes early.

Let voters track their ballots

In Oregon, each outer envelope, the one the voter needs to sign, has a unique bar code printed on it. That lets voters track the status of their ballots after they have either mailed them or dropped them off.

Be clear about deadlines

Some voters will always wait until the last minute to make their choices.

In January 2020, Oregon set up a system where voters don’t need to buy postage for the ballot envelope. All ballots must be received at county election offices by 8 p.m. on Election Day. So someone who is running late should probably avoid the mailbox and find a drop-off site instead.

Be ready for criticism

Mail-in voting is popular in Oregon, and, it seems, around the country.

But there are critics. Some are concerned that the system provides no guarantee of a secret ballot, but there has been no evidence that undue influence on voters, like bribes or threats, has been a problem in Oregon elections conducted by mail.

Others have falsely claimed there is more fraud with mail-in voting. Oregon has mailed out millions of ballots over the past three decades, with about a dozen cases of actual fraud. Most problems were unintentional errors involving signing the wrong mailing envelope or assuming that a voter could sign the mailing envelope for a family member.

My research, and that of others, has found that voting by mail boosts turnout modestly, especially in special elections and in years with presidential elections. Some people have raised more personal concerns about losing the ritual of going to the polls with other members of the community. It may be less social to vote at home, but more people’s voices are being heard.

Criticism is inevitable, but skeptics and supporters alike can look to the experience of Oregon for real answers. Perhaps the strongest evidence that the system is equitable, fair, reliable and safe is that in two statewide surveys I have conducted over the years, a nearly identical percentage of Oregon Republicans and Democrats strongly support voting by mail, and the same is true of elected officials in the state.![]()

—By Priscilla Southwell, Department of Political Science