Editor’s note: This article is republished as it appears in The Conversation, an independent news publisher that works with academics worldwide to disseminate research-based articles and commentary. The University of Oregon partners with The Conversation to bring the expertise and views of its faculty members to a wide audience. For more information, see the note following this story.

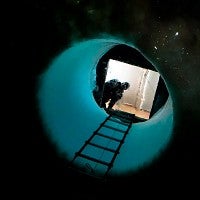

I’m sitting on the edge of a hole drilled through 15 feet of Antarctic sea ice, about to descend into the frigid ocean of the southernmost dive site in the world. I wear nearly 100 pounds of gear: a drysuit and gloves, multiple layers of insulation, scuba tank and regulators, lights, equipment, fins and over 40 pounds of lead to counteract all that added buoyancy.

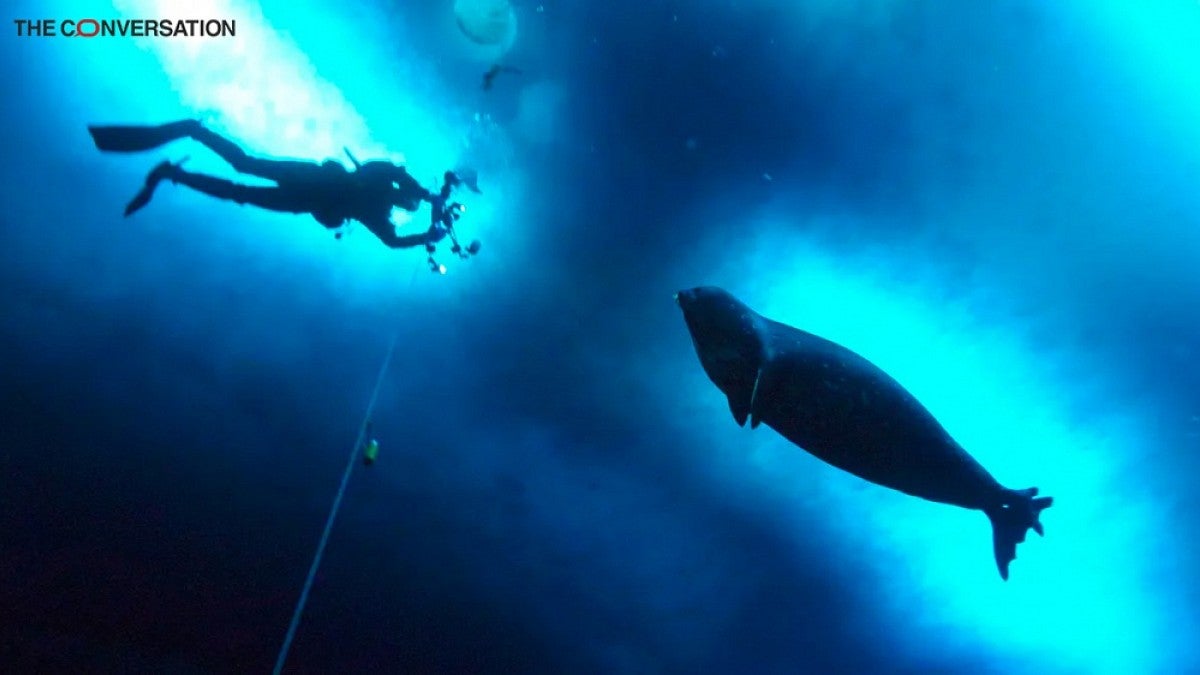

As we frog-kick along, following our lights toward the work site, a Weddell seal glides by with a few effortless undulations. It glances sideways at us a couple of times, as if doing a double-take.

In contrast to us awkward, gear-laden human divers, Weddell seals are completely at home under the ice. They can hold their breath for more than 80 minutes and dive to a depth of nearly 2,000 feet. Somehow they explore, find food and return to their isolated breathing holes even when it’s completely dark.

During my deployment to Antarctica in 2018, I participated in 40 such dives to help maintain the McMurdo Oceanographic Observatory. Polar marine biologist Paul Cziko installed the 70-foot-deep, seafloor-mounted recorder in 2017. Known affectionately as “MOO,” it resembled R2-D2 in both looks and charm. For two years, MOO successfully sent continuous audio, video and ocean data back to our onshore lab via cable connection. It also streamed a real-time view of this enthralling Antarctic marine ecosystem: ice glittering on the seafloor and ceiling, giant sea spiders and isopods creeping among the sponges and soft corals.

Surprising seal sounds

These newly discovered call types — nine in total, with base frequencies above 20 kHz and ranging up to nearly 50 kHz — are the first report of such high-frequency vocalizations in any wild seals, sea lions and walruses, the group of sea mammals collectively known as pinnipeds.

The MOO was the first long-term observatory of its kind, and its cutting-edge technology let us collect an unprecedented data set, including sounds with frequencies up to about 10 times higher than most previous studies.

Our discovery begs the question: What do the seals use their high-pitched ultrasonic calls for? One possibility is that they represent a form of active biosonar, similar to the echolocation used by bats and dolphins. That is, the returning echoes of their high-frequency sounds may provide information to the seals about their environment and potential prey.

Previous studies have argued that pinnipeds do not echolocate because they do not possess the specialized anatomy for producing or processing tightly focused sounds with very short time intervals. Additionally, their known calls don’t exhibit the telltale characteristics of echolocation pulses, such as accelerating in time as an animal approaches a target.

But the ability to use sound to “see” their surroundings would be especially useful during very low-visibility conditions, like what the seals encounter under thick ice or in the polar winter, when there is no daylight for four months. Our preliminary findings indeed suggested that the use of certain high-frequency pulsed vocalizations increased during the dark Antarctic winter. It is also very likely, and not mutually exclusive, that the seals use ultrasonic calls for communication, as has been shown for their human-audible calls.

Serendipitous discovery raises more questions

It’s still a mystery how seals navigate and forage under the ice in certain conditions. Weddell seals and other seals that live on the ice have many adaptations for diving and finding their breathing holes again, including good low-light vision, spatial memory and extremely sensitive whiskers, called vibrissae.

However, these senses each have their limitations. Sometimes there may be literally no ambient light where the seals are diving. Following the same routes on every dive would preclude finding new patches of mobile prey. And the tactile sensation provided by whiskers is only useful at close range.

Back in the lab at McMurdo Station, the MOO livestream ran as we worked at our desks. The ethereal trills and chirps of seals filled the air. During their Southern Hemisphere spring breeding season, vocal activity is nearly constant. A couple of monitors showed real-time graphical displays of the incoming data: ocean temperature, salinity, tides. A scrolling audio spectrogram would pull us in every so often, mesmerizing us with colorful squiggles that appeared as we heard the calls, a synchronized visual soundtrack.

Every few minutes, bright wiggles and lines would scroll by in the upper register, announcing sounds that we cannot hear. They are patterned; they are repeated again and again. They are seal voices. If we can decode them, they may tell us more about how these seals thrive in what we humans perceive to be a very challenging environment. As technology sheds new light into the depths, what else will we find?![]()

—By Lisa Munger, Clark Honors College