The Spy Who Taught Me

BY LAURIE NOTARO

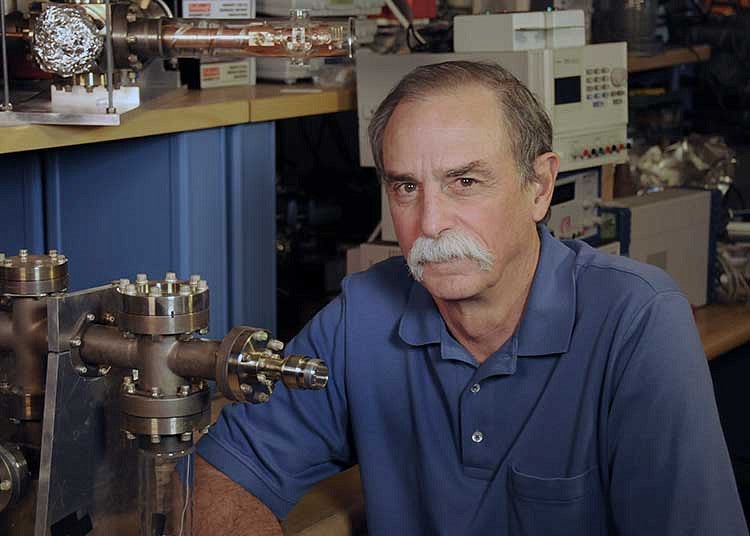

Former intelligence officer and UO professor featured in Ken Burns’ new documentary “The Vietnam War”

With the wide variety of expertise and backgrounds of UO professors, it is not surprising for students to discover that behind the lecture, there are backgrounds that include working on a cure for blindness, being honored with Emmys, Guggenheims, and Pulitzers, or lauded as the country’s leading expert on Beowulf or imaginary childhood friends. But settling into their seats at the beginning of every term, very few—if any—students would look up and see the English professor reading from James Joyce and imagine that once, the instructor had a price on his head.

For tens of thousands of UO students who took a class from George Wickes over the 62 years he was actively teaching, 47 of that here at UO, that was exactly the case.

It was 1945 in Saigon, and Wickes had been in Vietnam for four months, spending time getting to know the leaders of the Vietnamese movement that sought independence from France. Twenty-five years before Wickes joined the University of Oregon’s English department, he went about his business in Saigon, talking to people, asking questions, completely unaware that the French had made him a target.

George Wickes was a spy.

Wickes served in Vietnam after World War II, collecting intelligence information for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). While there, he experienced the death of his commanding officer, was engaged in a firefight against a band of guerilla attackers, and later interviewed Ho Chi Minh.

It was his OSS work during that time that caught executive producers Ken Burns’ and Lynn Novick’s attention when they were researching their 10-part, 18-hour PBS documentary, “The Vietnam War” that airs September 17. Wickes’ role in the Office of Strategic Services, which later evolved into the CIA, is featured in the first episode documenting the preliminary stages of the Vietnamese independence movement, which the US supported. Former students might be surprised to know of their professor’s role in history, but with a pedigree such as Wickes’, it should almost be expected.

“Well, yes, you could say I was a spy!” declares Wickes, now 94, in the living room of his Eugene home that is nestled on a hillside covered with towering pines. “The great thing about the OSS was how imaginative it was. Instead of following military protocol, OSS had no hesitation about breaking rules and doing things no one else did. The Navy SEALS, for instance, were conceived when the OSS decided to send swimmers into enemy harbors to sink ships by attaching explosive devices nicknamed ‘limpets’ to their bottoms.”

That was precisely the kind of knowledge that the producers of “The Vietnam War” were looking for; a surviving eyewitness, possibly the last, of the infancy of the United States’ involvement in Vietnam. Wickes’ name is included in virtually every available document about the history of the OSS.

"We knew when we started on the project that it was essential to capture the early American involvement in Vietnam, post the second World War,” said the film’s producer, Sarah Botstein. “When we learned that George Wickes, one of the only surviving members of his OSS team, was alive and well—and willing to meet with us —we knew it was urgent that we get on a plane. Not only was he one of a small number of Americans in Vietnam at the time, but the fact that he met with Ho Chi Minh, and had given a lot of thought to his experience in the country at that time, was hugely important."

Seven decades after his time as an OSS operative, Wickes recalls with pinpoint accuracy how he began his service as a cryptographer in Saigon, coding and decoding messages, but eventually began to collect information and report back to Washington, DC about unfolding events on the ground.

Because of his linguistic ability the Army had sent Wickes to Berkeley in 1943 to study Vietnamese. While there he passed a barrage of cryptology tests, which led to his being recruited by the OSS, trained as a cryptographer at Washington, D. C. headquarters, and sent overseas to Southeast Asia. Wickes was in Rangoon when the war ended and heard that OSS was sending a small team to Saigon under the command of Colonel Peter Dewey. He looked up Dewey and asked if he could join the team, explaining that he had studied Vietnamese. Dewey was unimpressed but asked if he could speak French. It was a matter of birth that made Wickes a consummate candidate; with a Belgian mother, French was his first language and he didn’t learn English until he started elementary school in Rochester, New York.

Despite Wickes’ assertion that he was fluent, Dewey gave him a one-question exam, requesting the French word for “street.”

“Rue,” Wickes replied, with the distinct, deep roll of the “r,” a notoriously difficult pronunciation that would easily indicate he was a nonnative speaker and blow his cover. Wickes was in, and was shipped off to Saigon to work with Dewey and the remainder of the OSS unit there.

Wickes didn’t discover that he was a target for assassination until he faced military charges of impersonating an officer after he returned stateside; Dewey was the real target, but he often sent Wickes to clandestine meetings in his place with Vietnamese leaders of the independence movement that the French were attempting to suppress, and the French had mistaken Wickes for Dewey. Because Wickes, whose rank was “enlisted,” was not permitted to meet with officers that held a higher rank due to military protocol, Dewey unofficially bestowed the field promotion to lieutenant to solve the problem. The charges eventually vanished.

Although the bounty was never collected on Dewey or Wickes’ head, Dewey was the first American soldier killed in Vietnam, mistaken for a French officer at a Vietnamese guerrilla roadblock as he was travelling to meet a plane to take him home.

“Dewey had wanted to fly the American flag on the jeep, but general Douglas Gracey had forbidden it, saying that only he as a commanding officer had the right to fly his flag,” Wickes writes of the account. “There was no way for the Vietnamese to know that this was an American jeep or that these were American officers.”

Dewey was killed instantly by gunfire; his Jeep rolled and his driver escaped, who, covered in Dewey’s blood, made it back to the OSS villa where Wickes and the rest of the unit were located. The OSS officers held the guerrillas off for hours until the guerrillas retreated.

Wickes, by then a close friend of Dewey’s, was charged with “the rather gruesome job” of recovering his commander’s body, which was never found despite numerous exhumations of human remains that were rumored to be Dewey’s.

After Dewey’s death, the unit moved from the villa to the Continental Hotel, which played a large part not only in OSS operations in 1946, but again in the Vietnam War where the main American news outlets such as Time and Newsweek housed their journalists. The landlord lived next door to Wickes and the OSS radio operator, helped keep their cover, and continually tried to coerce his spy neighbors into smoking opium to “loosen them up”; the landlord, Mathieu Franchini, was the largest opium dealer in French Indochina.

“He was happy to have Americans there to protect his property,” Wickes laughs. “He was always asking, ‘Come have a pipe with me.’”

Wickes determinedly never did.

Several months after Dewey’s death, Wickes and another member of the Saigon team proposed a mission to Hanoi to interview Ho Chi Minh to specifically ask if he was a Communist. The answer was an obvious “yes,” but Wickes surmises that OSS and presumably the State Department authorized the mission because they wanted to find out what was going on in Northern Vietnam; an earlier mission in Hanoi had been recalled and there was no American representative at the time.

To Wickes’ surprise, the interview was conducted in English; Ho Chi Minh had spent time as a young man working in restaurants in Boston and New York. He described his respect for the principles of the Declaration of Independence and told them the history of Vietnam and the beginnings of the independence movement.

“Ho expressed his admiration of this country,” Wickes said, “with which he wanted close ties and support for the independence movement.”

In his letters home, Wickes described Ho Chi Minh as, “short and very slight, a little stooped . . . a scraggly mandarin mustache and a wispy beard—all in all, not a very imposing man physically.

“But when you talk with him he strikes you as quite above the ordinary run of mortals. Perhaps it is the spirit that great patriots are supposed to have . . . But I think it is particularly his kindliness, his simplicity, his down-to-earthness. I think Abraham Lincoln must have been such a man—calm, sane and humble.”

After World War II, the OSS was becoming the CIA and the new organization wanted Wickes to join their ranks. He didn’t particularly care for the new outfit.

“And we weren’t at war any longer,” he adds. “The spirit of the CIA was different from the spirit of the OSS. The OSS was like a lark. The CIA sounded more sinister.”

He doesn’t think about what his life would have been like if he had joined the CIA, stealthily shooting around the globe and encountering “colorful characters with bushy mustaches,” he adds. “I just wanted to go to the University of California and study English some more.”

Wickes went to graduate school on the GI Bill, earning a master’s degree at Columbia University and a doctorate at Berkeley. He taught for three years at Duke University, then moved to Claremont, California, as one of the seven founding faculty members of Harvey Mudd College. After 12 years there, he came to the University of Oregon as a visiting professor of known publications on modern writers,

“It was a one-year appointment,” Wickes remembers. “The university and I looked at each other and decided to make it permanent.”

Wickes also directed the Fulbright program in Belgium, the place that had such a key role in determining his life’s path. He is the author of numerous books, including a biography of salonist Natalie Barney and Americans in Paris, a nonfiction narrative about expatriate writers in Paris during the 20s and 30s, and his own memoir, Memories. He also edited several editions of Henry Miller’s personal letters. Wickes has donated the materials and papers associated with his rich and varied history to the Knight Library, where they are available to view through Special Collections.

“It is amazing, really, that the quiet and contemplative life of a teacher and literary critic in Eugene, Oregon, could have appealed to George after his cosmopolitan upbringing, his international education, and his adventurous early career in Cold War era military intelligence," professor and former English department head Harry Wonham said of Wickes. "But tucked within his memoir I found subtle hints that perhaps he was really meant to be a critic from the very beginning.”

Wickes officially retired in 1993, but continued to teach until 2015, for a total of almost five decades. That equates to thousands of students, most of whom never knew their professor was once a spy. Wickes has still not abandoned his love of academia; he will be teaching an Insight Seminar through UO Academic Extension on F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway beginning in January.

To Wickes, the excitement, creativity and the purpose of his time in Vietnam is both remarkable and normal. Like every enlisted man who served in the war, he saw horrific things, experienced significant moments in history, and got first-hand accounts of how extreme life as a soldier, as a spy, could be.

But it wasn’t the spy life that was for him; it was always teaching, not passing on intelligence, secrets or ground movements, but knowledge of a different sort.

“I loved teaching most of all,” he said with a smile, settling back in the chair in his living room. “I just had the most marvelous career.”