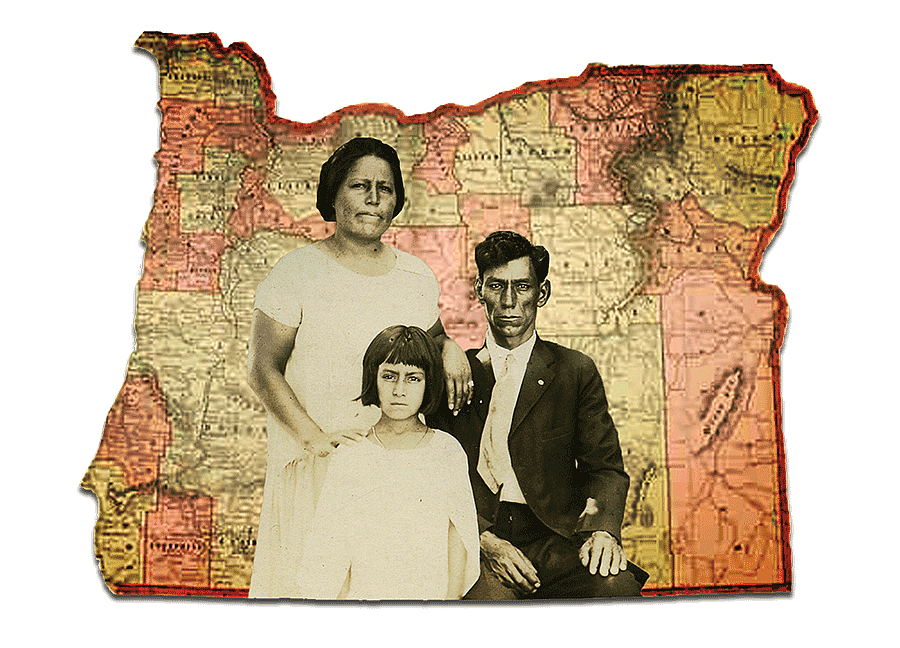

Latino Roots,

Oregon Branches

Latino Roots,

Oregon Branches

Latino Roots,

Oregon Branches

BY JASON STONE

You come to college to take classes like this one.

It’s part history, part sociology, part anthropology, part journalism and part documentary filmmaking, but it’s all about the experience. The 400-level Latino Roots course is an example of the many compelling, hands-on, educational opportunities we offer at the University of Oregon. With an eye on history and a hand in technology, this course combines the theoretical with the practical and empowers students to apply their new knowledge in the real world.

An intensive, two-term, 20-week course, Latino Roots is offered every other academic year. During the first term, centered in a formal classroom setting, students learn about the history of racial identity formation in Oregon. Next, the class moves to the Cinema Studies Lab in Knight Library for hands-on training in the use of audio-video technology and editing software, as well as learning the art of documentary storytelling.

“I’m blown away by how hard and fun it is,” said Juan Camacho, a nontraditional student majoring in anthropology. “And all those skills I didn’t have in the ‘real world,’ I can see now—‘Oh, so this is where you get those skills.’”

But the most powerful learning occurs when the students go beyond campus and out into the community—conducting audio interviews and shooting video footage of the underrepresented life stories of Latinos in Oregon for documentaries they create and showcase at an end-of-year celebration.

“We are helping to tell somebody’s story, trying to learn all about them,” said Roben Itchoak, a graduate student in community and regional planning who took Latino Roots in 2017. “And at the same time we are learning about ourselves, and how to express ourselves.”

Juan, who was both a student in the class and a participant in one of his classmate's documentaries, grew up in Redondo Beach, California, where his entrepreneurial mother founded a babysitting business that grew into a local institution. In many ways, his 1970s upbringing was generically Southern Californian.

“I’m a Mexican-American who got a B in Spanish in high school. I didn’t grow up specifically Mexican; in some ways I fought against that identity.”

Initially, Juan put off college to concentrate on The Detonators, a hardcore punk band he started with his best friend— a decision that would lead to a longstanding career in indie music. The first time the band came through Eugene on tour, Juan was smitten with the place and he moved here in 1987.

Touring a bit less these days at age 56, Juan is fulfilling a promise he made to his mother many years ago by earning his bachelor’s degree. And while at the UO, he has discovered a deep interest in cultural anthropology.

Back in his band days, in between touring gigs, Juan sometimes worked as a landscaper to make ends meet. When it came time to choose his documentary participant, Juan approached Mateo Amezcua, the landscaper who cares for most of the yards in his Eugene neighborhood.

“I’ve known Mateo for about five years,” Juan explained. “He’s been growing his business and we talk all the time. I was just fascinated because landscapers are the invisible entities in our neighborhoods.”

One important lesson Juan says he has learned—from anthropology, from punk rock, from his five-plus decades of living and from Latino Roots—“Identity needs to be validated by ourselves before it can be validated by the people we are up against.”

Romario Garcia Bautista, a third-year undergraduate student majoring in journalism and anthropology, points out that for many in the Latino community, the challenges of identity validation can be much more complex than outsiders often realize.

“When people think about Latinos, Latinas, Latinx, they often get this representation that everyone is the same and that everyone comes from the same background. But the word Latino is actually a really broad word.”

Romario, who was born and raised in the United States but also has an ancestral hometown in Oaxaca, Mexico, is of indigenous Zapotec heritage. He says that for indigenous Latinos such as himself—as well as for Afro-Latinos and other ethnic groups—experiences of discrimination can come not only from the dominant Anglo culture, but also from within the greater Latino community.

This awareness inspired his choice of Latino Roots documentary participant. “I wanted to interview someone who understood the struggle within indigenous communities,” he said.

The perfect candidate turned out to be someone he was already close to. During his freshman year at the University of Oregon, Romario met one of his best friends—Diego Vasquez Martinez, a computer and information science major who grew up in Oaxaca.

“We instantly clicked,” Romario recalled. “We’ve connected a lot because of our shared indigenous heritage. Our personalities are very different, but we’ve had a lot of the same experiences and we’re interested in a lot of the same things. We understand the same jokes and love the same foods. I was born in the United States, he was born in Oaxaca, so our experiences growing up as indigenous youth were different—yet they were also the same.

“When I was taking this course and interviewing my friend Diego, it brought up questions in my mind like, maybe I should interview my father, or my mother, or my relatives and better understand their experiences. This is just one story, and there’s millions of stories out there.”

Another student in the class, Brenda Garcia Millan also reflected on the complex issues of formulating and validating an authentic sense of identity in the 21st century. Brenda was born in Tijuana and moved to San Diego at age 15, and later became a U.S. citizen.

“I consider myself to be from the border, basically, because I spent half my life on one side and half on the other,” she said. “Even in Tijuana, culture is very Americanized. I grew up celebrating Halloween and Thanksgiving, and believing in Santa Claus.”

Currently a second-year graduate student in international studies, Brenda is researching crisis intervention among Haitian refugees settled in Tijuana. Finding her thesis subject was an eye-opening experience, because she had initially expected to focus her study on Mexican migrants when she began her research.

She’s also found living in Eugene to be a cultural eye-opener. “Since I moved to Oregon, that’s when I started noticing ‘Oh, I am a Latina living in the United States.’” Brenda had so many Latino friends and classmates in San Diego that she “never really felt like I was a migrant, even though I am.”

For her documentary, Brenda approached Edward Olivos, head of the Department of Education Studies.

“He is a second-generation Mexican-American who is a professor, but also an advocate for migrants,” she explained. “He works with people who have been deported, especially parents and military veterans. I decided to tell his story because he is a Latino who is in a position of power at a university, and he uses that position to create awareness on issues of deportation.

“I don’t want just to make a documentary that will get a good grade and pass the class—I want to make a documentary that will help his cause.”

“People of Spanish descent have been coming to Oregon since the 18th and 19th centuries and you will still find some Spanish place names on the coast,” observed Gabriela Martinez, associate professor in the School of Journalism and Communication who teaches the Latino Roots class in collaboration with anthropology professor Lynn Stephen. “So it is kind of mind-boggling to have the history of this community—12 percent of the state’s population—not being fairly represented.”

Nearly three decades before Lewis and Clark set out on their much-heralded overland trek to Oregon, the Spanish crown began sending ships from New Spain to explore the Northwest coast, and it wasn’t until 1819 that Spain ceded its land claims in the Pacific Northwest. Since that time, Stephen says, Latinos and Latino culture have been systematically marginalized within our region’s “official” history.

“The predominant framing of the history of the state has been a White pioneer narrative,” Stephen explained. “With Latino Roots, we conceptualized the idea that, in order to train students to be oral historians, journalists, documentarians and anthropologists, we would need to teach them about how Latino history fits into the larger racial and ethnic history of Oregon.”

Race and ethnicity. Identity and privilege. Diversity. Inclusiveness. These are some of the crucial issues of our time—even on a college campus, however, they are not always easy subjects to talk about.

“One of the most important things in this course,” Romario believes, “is just to be able to communicate with each other, to break down those walls of tension.”

Juan agrees. “In the Latino Roots class, you can tell people think about racism. It’s a really big topic. You can tell when no one wants to talk, but because we are discussing these things in the class, I think it draws out discussion and it forces you to think who you are.”

Stephen explains that not only Latino history, but the roots of Native American, Black, Asian-Pacific and Anglo-European experience in Oregon are surveyed by the class.

“The idea was to create this forum, to create a group with a common understanding of the history of race and of positionality—Who are you? What is your story? Where do you come from? Everyone in the class, regardless of who they are or what their personal experience is, has to go through that process of self-interrogation.”

In Latino Roots, cultural competency is half the equation. The other half is technical facility. From this conjunction of practice and reflection arise new understandings and real-world learning opportunities.

“I had just worked with basic cameras before, so it was my first time working with a professional-level Panasonic camera,” says Timothy Herrera, a graduate student in anthropology. “Coming from academia, you’re always working on research papers and problems, but you hardly ever get the opportunity to tell another person’s story. It requires a different set of skills.”

Martinez believes that these skills are not esoteric, but practical. “Media is such a powerful tool that it should be in the hands of more people, not just a restricted number of ‘experts.’ And that’s going to be valuable not only in the job market; we can use technology for the good of society and to better understand who we are as a nation.”

In other words, this course in documentary filmmaking isn’t meant just to put a camera in students’ hands—it is designed to make them more conscientious of where they are pointing it, and why.

Latino Roots Documentaries

All 15 videos produced by the 2017 Latino Roots class, with synopses and producer/director biographies.

Oregon Latino Heritage at Oregon Digital

Collection materials from the UO Libraries’ Special Collections and University Archives, including photos, videos and interview transcripts from past Latino Roots classes.

Oregon’s Latino Roots Library Research Guide

Books, articles, reference works and primary sources for further research and learning.

One more thing that makes Latino Roots a one-of-a-kind experience: when the class is over, the students and teachers celebrate together!

The Biennial Latino Roots Celebration is a standing-room-only event. Faculty, administrators, community leaders and diverse supporters come together in Knight Library’s Browsing Room to acknowledge the achievements of the student documentarians and honor the history of Latino people in Oregon.

“Latino Roots is incredibly valuable because you are documenting who you are and where you are from, not only for you, but for us,” said President Michael Schill. “This program is focused on the fastest-growing segment of our state and our country. What you are doing allows us to connect with families of young people who will become our future students.”

Following the ceremony, copies of all the videos, interview transcripts and supporting materials are placed in the UO Libraries’ permanent collection, ensuring that future generations always will be able to access and learn from these important historical records.

Estas raíces corren profundamente—These roots run deep!

Latino Roots Student Videos