As one of the most unusual incidents in Oregon’s recent history is gaining renewed attention through a hit Netflix program, discussions about Rajneeshpuram have also been rekindled on the UO campus.

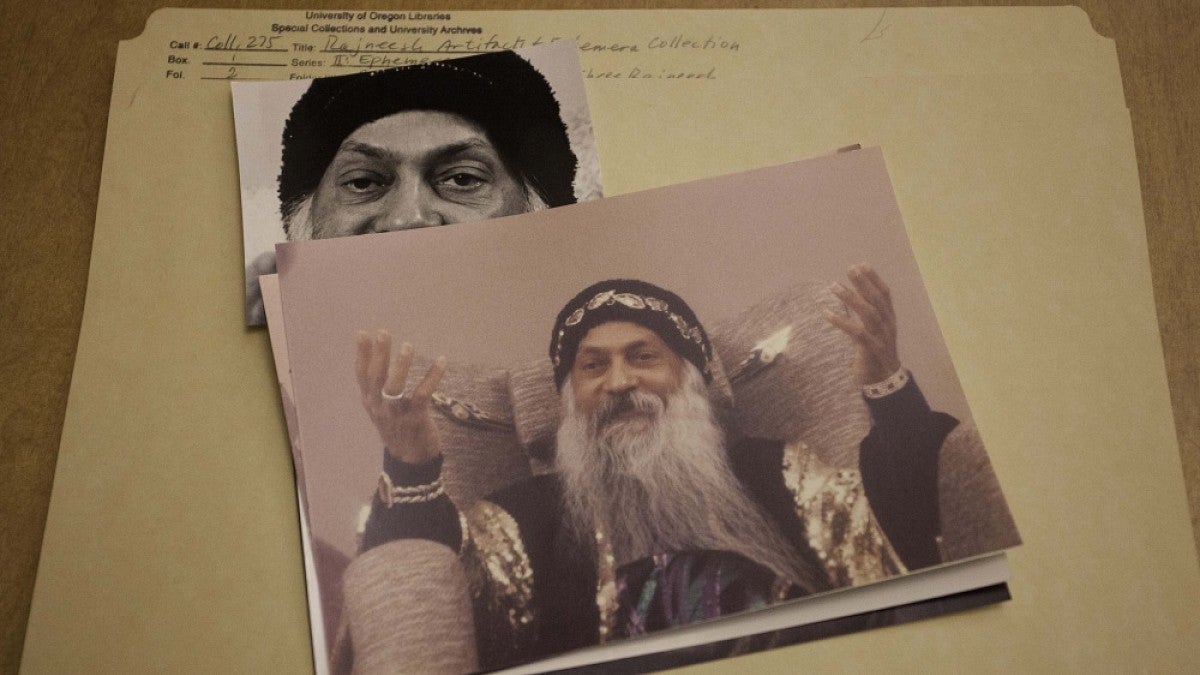

For viewers whose interests were piqued by the series and want to learn more, the UO Libraries’ Special Collections and University Archives holds a definitive collection of historical documents and artifacts related to Rajneesh and makes these resources available to the public as well as scholars and researchers.

Debuting March 16, the documentary series “Wild Wild Country” tells the story of the conflicts that arose when the controversial Indian spiritual leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and thousands of his devoted followers attempted to establish an intentional community in rural Central Oregon.

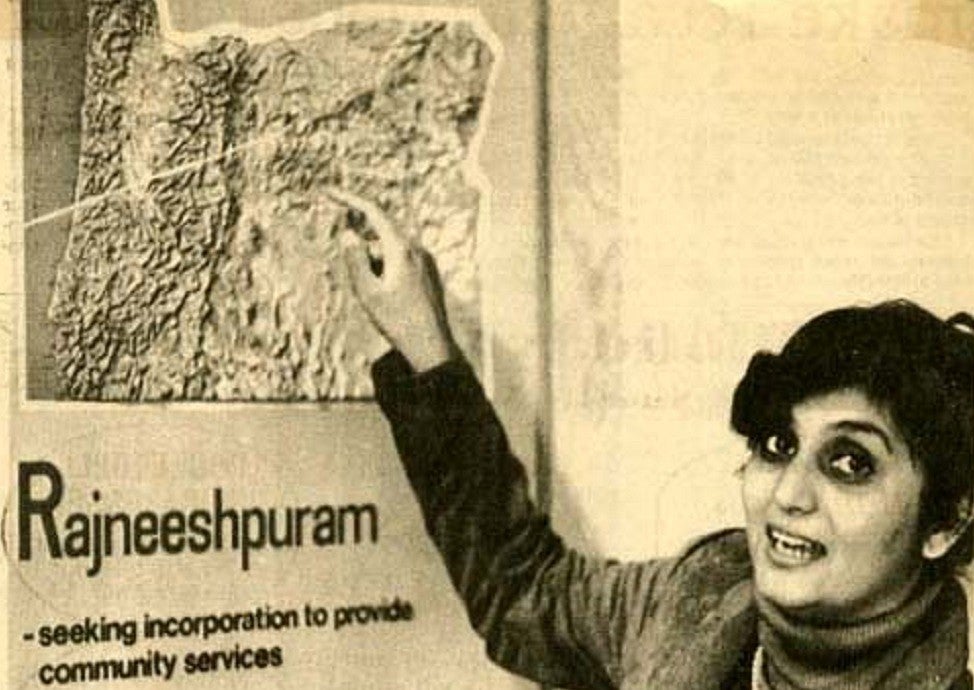

In 1981, group members purchased a 64,000-acre property near the small town of Antelope. Their ambition was to raise a permanent city, Rajneeshpuram, from the ground up on the arid ranch land. They quickly succeeded in establishing a thriving community. However, it didn’t take long for tensions to arise between the newcomers and some longtime residents of Wasco County.

Public figures including Dave Frohnmayer and Bill Bowerman became involved and, within just a few years, the conflicts would escalate from legal battles over land use issues to allegations of illegal surveillance, arson, attempted murder and bioterrorism.

Marion S. Goldman, UO Professor Emeritus of sociology and religious studies, is an expert on new religious movements and author of “Passionate Journeys: Why Successful Women Joined a Cult,” a critical study of the Rajneeshpuram phenomenon.

“For my book, 'Passionate Journeys,' I visited Rajneeshpuram for a total of 30 days before it closed down completely in 1986 and talked with almost a hundred men and women,” Goldman said. “I also interviewed devotees in Portland, Eugene and Salem, as well as a number of ranchers and Antelope residents during the early 1980s.”

Goldman confessed that, like many others, she recently got caught up in binge-watching all six hours of the “Wild Wild Country” Netflix series.

“My overall impression is that the documentary was beautifully done," she said. "It’s got a great narrative hook — irreconcilable differences, and only through good luck was violence avoided.”

However, Goldman also noted that some choices made by the producers have rendered their version of the story less than complete.

“Their major sources seem to have consisted of the most sensationalized news clips of the day," she said, "and some of the interview subjects they picked as major spokespeople tried to justify their own actions.

“Also, there’s nothing substantive about Bhagwan’s teachings and philosophies that drew so many people — including a large number of high-achieving women — to his work and to Rajneeshpuram. I wish there had been more time devoted to the ordinary followers who might have provided more perspective on day-to-day life in the community. In many ways this was not a stereotypical “cult.” Tourists were welcomed, and residents were free to come, go and host visitors.”

At the same time, Goldman said the historical record makes clear that Rajneeshpuram committed many violations of Oregon land use statutes and that some community members, including leaders, eventually were convicted of far more serious crimes.

“Dave Frohnmayer (attorney general of Oregon at the time of the controversy) and the attorneys in his office were committed to implementing consistent communications and the rule of law," she said. "Frohnmayer’s opinion on the city of Rajneeshpuram’s violations of the constitutional separation of church and state was vital in bringing a peaceful denouement to the Rajneesh years. Moreover, his patience and meticulous implementation of the law safeguarded everyone involved. It was a model of restraint.”

For serious researchers as well as the merely curious, Goldman pointed to UO Libraries as a great resource of information.

“Special collections houses the most balanced, comprehensive collection of manuscripts, publications and ephemera of the Rajneesh years in Oregon,” she said. “It balances materials from opponents with official Rajneesh documents and personal communications from non-Rajneesh supporters.”

Linda Long, UO Libraries’ curator of manuscripts, worked together with Goldman to assemble many of the collection materials over a period of years. In 2004, they videotaped a day-long interview with Sheela Birnstiel, also known as Ma Anand Sheela, at her residence in Switzerland. And in 1999, they were among the last people to visit the Rajneeshpuram property before it was transferred to new owners.

“We saw the console where they did all the wiretapping,” Long recalled. “In Sheela’s bathroom there was a button she could press that would lock all the doors into the building. There was a false back in the closet in her hot tub room, with a steep ladder that went down to the basement where they brewed the salmonella culture. We were down there in the dark and Marion backed up against a bookcase — and it springs open, too! It was sort of like being in a Nancy Drew mystery.”

Goldman said the library collection will have enduring value for researchers because Rajneeshpurum was more than just an eccentric episode of the 1980s. Rather, it reflected a longstanding dynamic in the culture of the state and region.

“Oregon has attracted communal groups for over two centuries because there is no dominant church, and until the 21st century land was relatively inexpensive," she said. "From the Jesus People (Shiloh Youth Revival Movement), to Lesbian Lands and Alpha Farm, alternative cultures and intentional communities have helped shape the state’s history.”

That Rajneeshpuram has re-entered the national consciousness and rekindled conversations more than three decades after the community was shuttered has not come as a complete surprise to Goldman.

“For a while I thought this was an event that had been submerged in history, because in the end nobody died," she said. "But the public always seems to come back around to an interest in cults, and for people who are millennials it’s a fresh story.”

(Read Marion Goldman's account, "I did research at Rajneeshpuram, and here is what I learned," at The Conversation.)

—By Jason Stone, University Communications

All images courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives, UO Libraries