The Oregon Center for Volcanology has grown into an international academic powerhouse

If your idea of studying volcanoes is peering over the rim at the top, you need to walk away from movie thrillers such as “Dante’s Peak” and “Pompeii.”

Some volcanoes erupt violently like Italy’s Mount Vesuvius did in 79 A.D., burying Pompeii. The 2010 blast from Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano shut down air traffic across northern Europe. “Dante’s Peak,” a 1997 fiction film featuring Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton, was set in a small town near a volcano in Washington’s Cascade Range.

And there’s Mount St. Helen’s dramatic eruption in 1980 that scattered ash across Portland and dramatically changed the landscape around the volcano. As 2020 began, 81 volcanoes around the world were showing signs of unrest. In January, eruptions in Ecuador, Mexico and the Philippines made the news.

Volcanoes come in all sizes, shapes and activity, says University of Oregon volcano scientist Paul Wallace, who has been using various techniques to study them for more than 30 years. The big challenge for researchers is understanding what happens below the surface, where they cannot actually go.

From the birth of its volcanology program in 1965 and its declaration as a cluster of excellence in 2014 – followed in 2016 by a $10 million gift from Gwendolyn and Charles Lillis to endow additional research positions – the UO has been probing every aspect of volcanoes – from the formation and movement of magma to various lava chemistries to the different types of eruptions.

“Oregon’s a great place to study volcanoes. There are unlimited possibilities here.”

Along the way, the UO’s 13-member Oregon Center for Volcanology has become an international powerhouse. It is the largest dedicated academic group devoted to volcanoes in the United States. Its members work across disciplines with each other and with colleagues in the U.S. Geological Survey and scientists at other universities. To date, 68 doctorates have been awarded to those who’ve studied volcanology at the UO.

“There have been number of great students and faculty members come through the UO over the years,” says Josef Dufek, director of the center that is part of the Department of Earth Sciences. “Our current cohort of faculty has expertise in a range of subfields in volcano science and together the group spans the discipline in an unprecedented way for a U.S. academic institution.”

UO scientists combined regularly have some 20 undergraduate students and more than 20 graduate students, working on such things as developing and testing sophisticated computer simulations, analyzing materials in their labs, or working out in the field gathering samples and taking measurements at various volcanic sites.

UO researchers have footprints at volcanoes around the world, including the nearby backyard laboratory. The Cascade Range through Oregon and Washington includes 10 major volcanoes. And there’s Mount Shasta and Mount Lassen in Northern California. Ten of these volcanoes are on the U.S. Geological Survey’s list of "most likely to blow and endanger people."

Among those sites is Newberry volcano near Bend, where UO researchers have been active for years. Newberry, which last erupted 1,300 years ago, has more than 400 vents and can generate flows of lava similar to Kilauea in Hawaii.

“These hires will enable the university to capitalize on one of its proven strengths. Gwen and I have been inspired by the great work of our volcanologists. We see this as an investment that will accelerate their research here and will ultimately lead to greater safety for those that live in the arc of active volcanoes.”

Last September, a New York Times story noted a lack of monitoring at Mount Hood, the towering behemoth east of Portland that last erupted in the 1780s. UO researchers are working at Three Sisters, east of Eugene, with an approach that could help efforts at Mount Hood and feed into the U.S. Geological Survey’s efforts to build a National Volcano Early Warning System.

“As the world’s population continues to grow and become more interconnected, it’s becoming more important to understand volcanoes,” Dufek says. “And the ability to forecast eruptions and the disruptions they cause is in its infancy, compounded by uncertainty.”

There’s a lot for current and future UO students to study.

“The Cascade volcanic arc running from Canada to northern California includes more than 2,300 volcanoes, ranging from large stratovolcanoes, to calderas formed by powerful explosive eruptions, to small cinder cones like those dotting the landscape in the McKenzie Pass region,” says former center director Paul Wallace. “And with active submarine volcanoes just offshore of Oregon on the Juan de Fuca plate, and the High Lava Plains to the east of the Cascades, Oregon has just about every type of volcano, volcanic eruption style, and lava type that you find worldwide.

“Oregon’s a great place to study volcanoes,” Wallace says. “There are unlimited possibilities here.”

With plate tectonics expanding research opportunities, center founders took advantage of the region’s volcanoes-rich landscape

Areas of Volcanology Research

Geochemistry

Geodynamics

Textural Analysis

Geophysics

High-Performance Computing

UO Researchers Study Volcanoes Around the World

UO's Volcanology Program By the Numbers

Volcanology Alumni

David Draper, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Studying volcanology at the University of Oregon helped launched Dave Draper into the role of deputy chief scientist at NASA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Draper said that he learned the basics of how magmas form through the UO’s strong multidisciplinary approach, which guides his present-day curiosity about volcanic formations on other planets.

“We have no choice but to attack problems from every angle we can,” said Draper, who arrived at the UO in 1985 and left with a doctorate in 1991. “Fortunately, the same physical chemistry happens on other worlds as happens on Earth. It’s just the compositions that are somewhat different. So, the training I had at Oregon directly applied to the studies I performed later in my career.”

A California native, Draper was drawn to Oregon’s natural laboratory for studying volcanoes after graduating from Humboldt State University with a bachelor’s degree in geology. He initially studied the geochemistry of lava rocks under Gordon Goles, one of the first members of UO’s volcanology program. He completed his doctorate under the supervision of Dana Johnston.

“I became interested in how laboratory experiments at high pressures and temperatures could help understand what goes on in the source regions in Earth’s mantle that generate these magmas, and this was the type of work in which Dana specialized,” Draper recalled.

“My fellow students were wonderful to work and interact with, and we had a pretty close-knit group during those years,” he said. “It was also exciting to witness the beginning of the expansive growth of the department as it leapt to the forefront of top-tier research institutions in our field, where it has remained ever since.”

Draper’s UO work resulted in a two-part dissertation in which he focused on volcanic activity in central Oregon and on high-pressure-phase equilibrium experiments on materials from an active volcano in the central Aleutians.

Before taking on his current NASA role, Draper led the Astromaterials Research Office, a division of the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Recent Alumni

Celeste Mercer

Heather Wright

Kathryn Watts

Ben Andrews

Where Are They Now?

Numerous other graduates of the UO’s volcanology program, which has awarded 68 doctoral degrees, have moved on to distinguished careers. Among them are William Leeman at Rice University, who earned a doctorate in 1974, Cal and Melanie Barnes at Texas Tech University, who earned their doctorates in 1982 and 1981, respectively; Dennis Geist, PhD ’85, now a program director in the Division of Earth Sciences at the National Science Foundation; Jon Castro of Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, who earned a doctorate in 1999; and Richard Naslund of State University of New York, Binghamton, who earned a doctorate in 1980.

Recent UO doctorate-earners, Celeste Mercer and Heather Wright, both now with the U.S. Geological Survey, were honored in 2019 with presidential early career awards – the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding scientists and engineers beginning their independent careers.

In addition, other UO doctoral graduates are now working at the Carnegie Institution for Science (Diana Roman, PhD ’04), University of Hawaii (Julia Hammer, PhD ’98), Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Adam Soule, PhD ’03), Middlebury College (Kristina Walowski, PhD ’15), Montana State University (Madison Myers, PhD ’17), Lawrence Berkeley Labs (Eric Sonnenthal, PhD ’90), University of Bristol (Allison Rust, PhD ’03), New Zealand Geological Survey (Natalia Deligne, PhD ’12), Exxon-Mobile (Stephanie Weaver, PhD ’12), GE Global Research (Dan Ruscitto, PhD ’11), New Mexico State University (Emily Johnson, PhD ’08), and Mexico’s Instituto Politecnico Nacional (Julie Roberge, PhD ’05).

UO undergraduates who went on to earn doctorates elsewhere and go into scientific careers include Edward Vicenzi, MS ’85 (geological sciences), now at the Smithsonian Institution; Marc Hirschmann, MS ’88 (geological sciences), University of Minnesota; and Alan Boudreau, MS ’82 (geological sciences), Duke University.

Birth of the Oregon Center for Volcanology

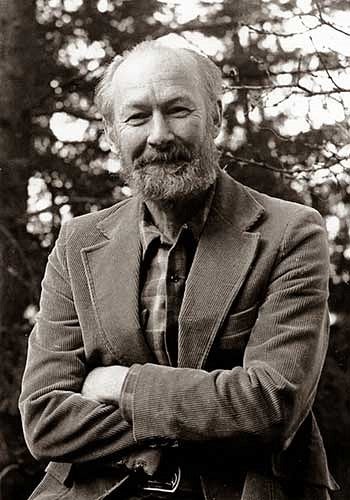

Volcanology at the UO began more than 50 years ago, exploding under the leadership of a former coffee farmer in Nicaragua.

The farmer was Alexander McBirney, whose crop suffered from ash falling from a nearby volcano and sulfuric gas percolating from underground magma vents. McBirney became intrigued by geology, eventually becoming one of the most prolific and productive pioneering researchers focusing on rock types created by magma.

His path to the UO as the founding director of volcanology research in June 1965 evolved slowly.

He graduated in 1946 from West Point Military Academy and went to post-war Europe, but he found military life was not for him. A chance invitation from his West Point classmate Anastasio Samoza Debayle to visit him in Nicaragua introduced McBirney to Central America and set him down the path to developing a coffee plantation in this volcanically active region.

Somoza Debayle would later follow in his father’s footsteps, rising to leader of the Central American nation. Volcanic vents on his coffee plantation, however, led McBirney elsewhere. He became, for a while, a prospector.

He soon befriended Howel Williams, who was doing field studies in Nicaragua as one of the world’s leading authorities on volcanoes. McBirney followed Williams to the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned a doctorate in 1961.

It was the dawn of plate tectonics. At the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, McBirney was among the early users of sonar to study mid-ocean ridges.

Barely four years later, the UO reached out to Williams, who pointed to McBirney as the best person to lead the UO’s volcanology program.

McBirney accepted the challenge, bringing Scripps colleagues Gordon Goles and Dan Weil with him to the UO. At their doorstep was Oregon’s wealth of volcanoes, especially those in the Cascadia subduction zone – part of the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire.

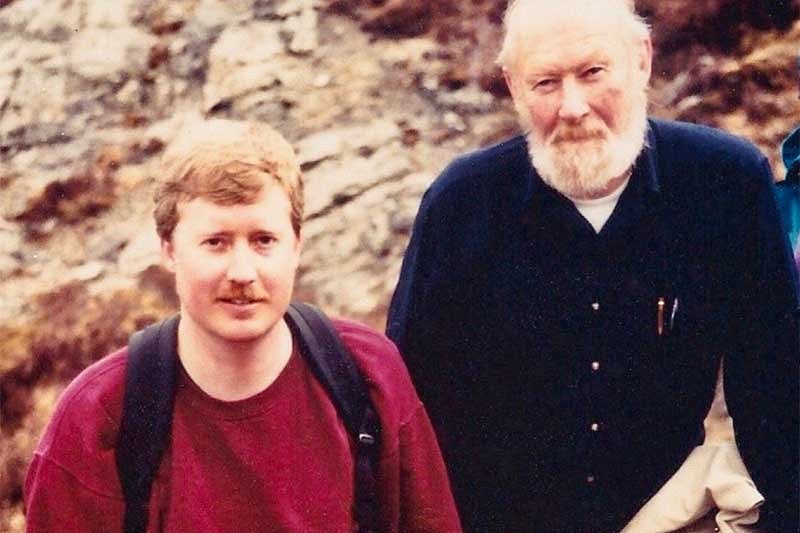

“We had a new center for volcanology,” said Dana Johnston, now a professor emeritus, who joined the team in 1986 and organized a remembrance for McBirney when he died in April 2019. “It was a concept, a dream, in the department’s collective mind that we could be big in the field of volcanology. The UO’s leadership asked McBirney to come here and bring the concept to life.”

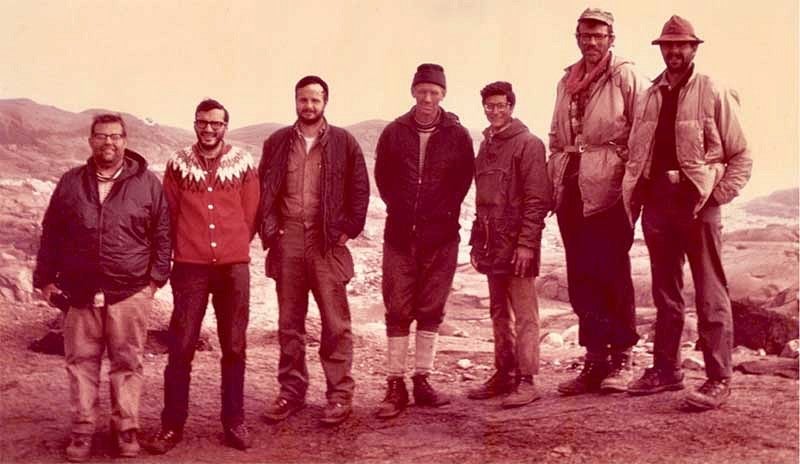

McBirney’s research in Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands and in Greenland, earned him – and the UO – swift recognition. He instilled an interdisciplinary approach, blending geophysics, geochemistry and petrology. He was a pioneer in understanding the composition of lava and other volcanic materials, mapping a course for such research around the world.

“McBirney was influential in thinking about subduction zones and their relationship with volcanoes,” said Josef Dufek, the UO’s Lillis Professor of Volcanology and current director of the Oregon Center for Volcanology. “This fell into the idea that volcanoes were tied to the regime of plate tectonics, which at the time was revolutionary thinking.”

McBirney, who spoke four languages, helped the UO land funding opportunities from NASA’s Apollo program and facilitated the UO’s becoming was one of the first universities to receive samples of moon rocks for examination. Based on their composition, McBirney made his own line of synthetic lunar lava, which he used to identify the differences between lava on the moon and Earth.