With fall and winter term behind them, faculty and administrators at the University of Oregon are reflecting on ways to increase the benefits of the Online Course Initiative and mapping out steps to give sudents more academic choices in the future.

“We launched the Online Course Initative to invest in the UO’s teaching mission and community in a time of crisis by providing training and support to rapidly develop engaging, well-designed versions of some of our largest courses,” said Executive Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Janet Woodruff-Borden, whose team developed the initiative, a push to develop 150 high-enrollment courses for asynchronous online delivery. “In selecting the courses for development, we worked in partnership with schools and colleges to expand online offerings strategically for student success going forward.”

Discussions about how to reach more students through additional online courses began in spring 2020 as the UO pivoted to delivering most of its courses remotely or in other forms when the pandemic hit. The initiative was led by Carol Gering, associate vice provost of UO Online, and Lee Rumbarger, an assistant vice provost and director of the UO’s Teaching Engagement Program.

By summer 2020, the UO was holding workshops where instructors and faculty fellows in mentorship roles co-designed the core courses with support from UO Online’s instructional design team. More than 120 UO faculty members engaged in the process.

Courses they developed were taught in fall 2020 and winter 2021, and they continue during the current spring term. A total of 167 online course sections resulted from the effort.

Faculty members who took part said they faced challenges putting courses together, given the pressure of the pandemic. But the initiative helped them in other areas. Many said the initiative offered professional development opportunities that went beyond online delivery skills, allowing them to better organize and elevate their course content in ways that would carry through all their teaching.

“Courses can have trememdous inertia because these big-scale changes are extremely time consuming,” said Nicola Barber, a biology instructor and faculty fellow in the initiative who also developed her own Biology 211 course. “That required modality shift presented this key opportunity to support faculty in revisiting their course.”

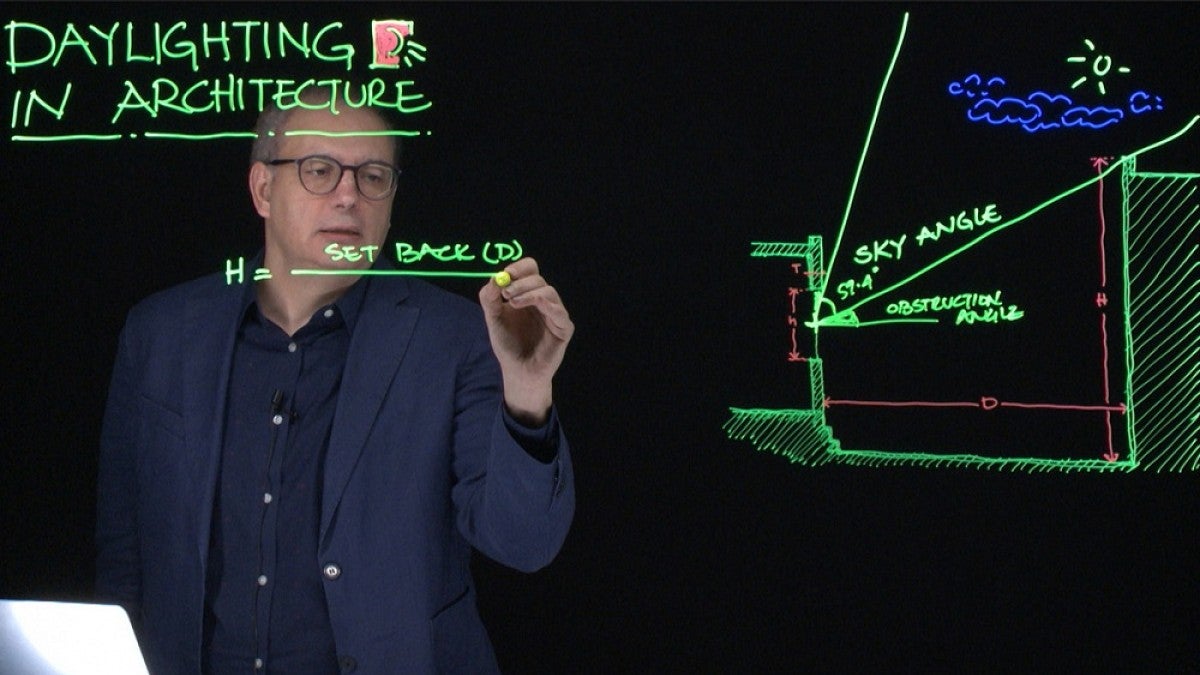

For associate professor Daisy-O’lice Williams of the College of Design’s School of Architecture and Environment, teaching Architecture 202: Design Skills through the initiative allowed her to take a different approach. She was able to structure her drawing assignments so they followed a particular pattern, which became very helpful, she said, because “students can latch onto that expectation and the rhythm of the assignments.”

Organizing that way also helped her pare down her course assignments.

“Having a much more clear intention and purpose behind the assignment, and a much deeper connection between how the assignments work together, has helped me refine the course material quite a bit,” she said.

Associate professor James Watkins, who teaches Earth Science 101: Exploring Planet Earth, found that using a modular course design worked well, and his instructional designer helped him translate that structure into Canvas.

Watkins was able to break up longer lectures into approachable 10-minute chunks, and the initiative introduced him to Bloom’s Taxonomy, a tool for defining learning objectives which he said “forces you to think deeply about what you want students to get out of a particular lesson.”

Among the benefits teachers noted that extended to students was the accessibility and flexibility the initiative afforded. Many said the ability to pause, rewind and rewatch prerecorded lectures would help students absorb more.

The enhanced flexibility of the online platform reached a large population, with 64 percent of the UO’s registered undergraduates enrolled in at least one of the initiative courses this academic year.

Jordan Pennefather, an experienced online instructor who teaches psychology, served as a faculty fellow for the initiative. He said asynchronous courses make scheduling conflicts with other aspects of students’ lives immensely easier to overcome.

“I think this initiative demonstrated that you can have a really good course with great integrity and student and faculty interaction and still be really engaging, so that you’re not losing anything by taking online courses,” he said. “They shouldn’t be easy courses. They should be enjoyable, thought-provoking courses that feel easy because you don’t have to show up to class twice a week.”

Interaction in an asynchronous setting is an ongoing challenge. But tools like active discussion boards, short videos to clarify common questions, virtual intercollegiate conferences, and collaborative assignments helped bridge the virtual gap.

Williams pointed out that though traditional verbal communication may be harder in the remote setting, that doesn’t mean it’s not happening in other ways.

“What we define as engagement has to open up; it looks a little different,” she said.

One of the best parts of the summer workshop was seeing how colleagues in other disciplines approached the same goals, according to several faculty members.

“At our core, our conversations were about good teaching; not good teaching online, but, ‘What is good teaching in philosophy? What is good teaching in journalism?’” said Nick Recktenwald, a senior instructor in English who served as a faculty fellow. “It’s really useful for me to learn a little bit too about how other faculty approach the writing process in their classes.”

Student success was a major objective Barber said she put particular focus on through the initiative.

“Introductory science courses are notorious barriers to student success,” she said, “and this online course initiative really helped in that capacity.”

In spring of 2020, Barber conducted a survey that identified five major obstacles. After the initiative, she surveyed her fall 2020 students about the same issues the spring students had raised: motivation, interaction or communication, ability to learn effectively, access to appropriate study space, and expectations for remote learning from instructors.

In the spring, as many as 75 percent of students surveyed reported negative effects in those areas. By fall, that same share of students enrolled in the course she developed through the initiative reported improvements in the same areas.

—By Anna Glavash Miller, University Communications