How the human genome gets transferred to each generation of offspring, and why things sometimes go wrong, are questions that occupy UO biologist Diana Libuda.

“Think of our genetic information as a cookbook composed of letters that make a recipe,” Libuda said. “We're passing those recipes down to the next generation and we want to make sure that the recipe is accurate because if you change it, it’s not going to be the same dish.”

Libuda will share some of the insights from her research in a Quack Chats pub talk at 6 p.m. May 23 at the Ax Billy Grill & Sports Bar at the Downtown Athletic Club, 999 Willamette St. in Eugene.

In her talk, “It’s Getting Hot in Here — Why Sperm Can’t Handle the Heat and What Biologists are Discovering About Genetic Inheritance,” Libuda will focus on one of her research projects examining why an increase in temperature can cause damage during sperm development and lead to male infertility.

“Of all the tissues in your entire body, including developing eggs, sperm are unique,” Libuda said. “They are the only ones whose genome cannot handle increases in temperature.”

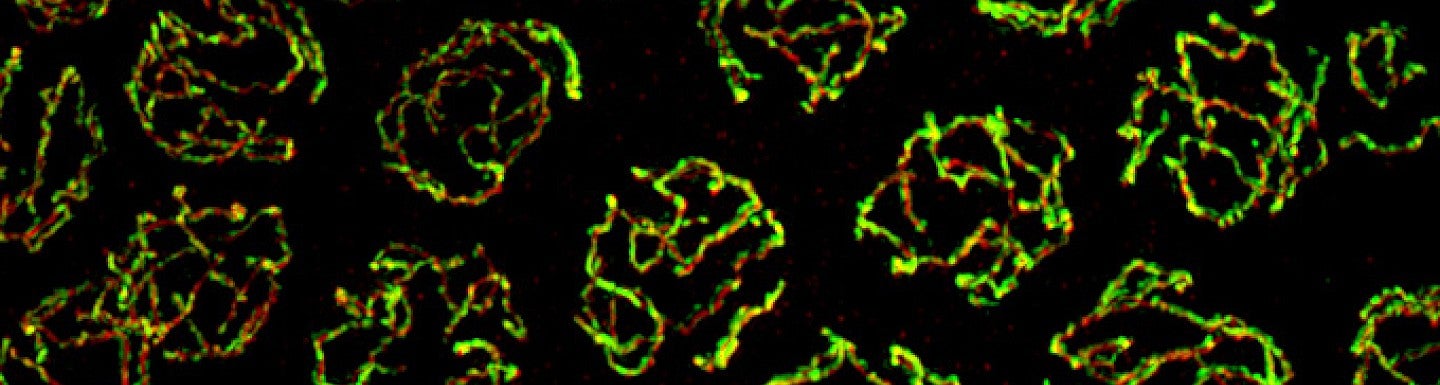

Libuda received her doctorate from Harvard University and her bachelor’s degree summa cum laude at the University of California, Los Angeles in molecular, cell and developmental biology with a music history minor. She is a key member of the UO’s Center for Genome Function, a group of molecular biologists studying fundamental problems in genetics and epigenetics.

Libuda hopes her talk will leave attendees with an appreciation for how the process of conducting fundamental science can affect human health. Among other things, she will talk about how scientists effectively make use of research using model systems such as nematodes, fruit flies, yeast, mice and zebrafish and look at the history of human genetics — not to mention the future, too.

“There are new technologies that are getting developed that allow us to very quickly and easily study the genetics and mechanisms behind fundamental questions in biology,” she said. ““I think it’s a very exciting time to be a scientist.”

For information about Quack Chats and to sign up for advance-notification emails, see http://uoregon.edu/quackchats. To learn more about upcoming Quack Chats, see the Quack Chats section on Around the O. A general description of Quack Chats and a calendar of additional Quack Chats and associated public events also can be found on the UO’s Quack Chats website.

—By Lewis Taylor, University Communications