Remembering Nepal

BY CHAKRIS KUSSALANANT

It is a question many have heard as a test of priorities: In the middle of a disaster what things would you remember to save? When a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Kathmandu, Nepal, around noon on April 25, 2015, Dristi Manandhar thought of only one thing—her family.

“Where is everybody? That was the first thing that struck my mind when the quake happened,” recalls Manandhar, now a second-year graduate student at the University of Oregon, who was at her parents’ home at the time.

Manandhar got out of her bedroom during the quake and managed to lead her parents and younger sister to safety outside of their house. Once the shaking stopped, it became clear for the Manandhar family how blessed they were, finding safety together and seeing their home standing unscathed. They also came to realize how much the rest of their homeland had suffered.

As the hours and days following the earthquake unfolded with a series of strong aftershocks, the extent of the devastation rose to unreal numbers: more than 8,000 dead, 21,000 injured, 40 percent of the country’s infrastructure damaged and nearly 505,000 homes destroyed.

The earthquake even caused an avalanche on Mount Everest, killing 22 climbers and guides — the deadliest day in the mountain’s history. Hundreds of thousands of people were made homeless, with entire villages flattened across many districts of the country.

“Everyone was displaced, as the earth kept shaking for 7 to 10 days,” Manandhar said.

Manandhar would come to experience a number of life lessons in the aftermath of the earthquake that would fundamentally shift her thinking. After graduating with an undergraduate degree in architecture from Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, Manandhar went to work as an architect. But she yearned for more professional experience long before the earthquake.

“I thought I needed experience outside Nepal, so I started looking at graduate school,” she said. “Then the earthquake happened and … I forgot that I’d applied to universities.

The quake’s magnitude, and its grueling aftermath, with collapsed buildings and piles of rubble, “changed something in me,” Manandhar said. “That’s when my perception of architecture changed, I realized how buildings can help people, but they might also kill people as well.”

In the days after the quake Manandhar became very focused. She contacted a number of colleagues, and soon she was recruited into the Nepal Engineering Association, a professional group formed by structural engineers, architects and designers who began the assessment of Nepal’s infrastructure. However, it did not take too long for the young architect to feel impotent and dismayed.

“We were going into these houses, and what broke my heart was telling people who had put all their savings into their homes that their homes had become a death trap,” Manandhar said. “I wasn’t helping, I was just giving them bad news.”

After one week and reviewing 300 homes near Kathmandu, Manandhar stepped away from the assessment effort. She then tapped six architecture alumni from her university to join forces designing an emergency shelter solution for their country. The team adopted the name Aashraya, which in Sanskrit means shelter.

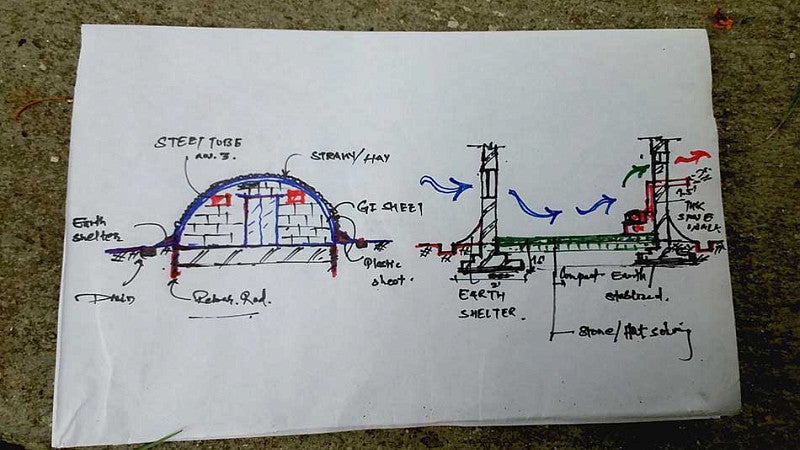

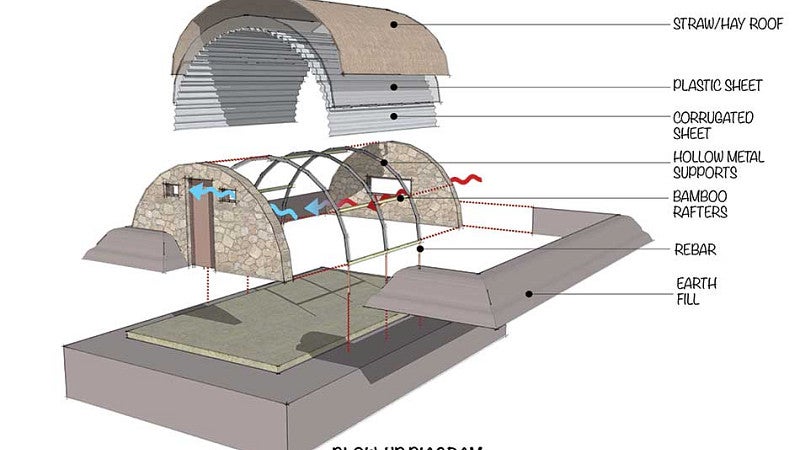

The team of designers quickly set out to draw plans for an economical transitional shelter that not only could withstand the coming rainy season but also Nepal’s strong winds. In a matter of two days, they came up with a dome design inspired by the work of Eli Kretzmann, a tour operator who in 2010 created a shelter to bring relief to millions after a flood in Pakistan.

The dome has three metal pipes bent into arches and arranged in a row. The rods are driven into the ground, and then nine corrugated tin sheets are placed over the arches, creating an 11-by-12-foot dome, which is tied up with wires to prevent the high winds coming off the Himalayan foothills from blowing away the shelter. The open sides can be closed with tarpaulin, brick or stone. Some Nepalese villagers even opted to add their local construction techniques, such as placing mulch or thatch atop the corrugated roofs to protect from heat and cold.

“One dollar is about 105 Nepalese rupees. With just $300 you can build two temporary shelters,” Manandhar said. “The whole thing takes just three hours for two people to build and all the materials are reusable.”

Aashraya shared the plans with as many organizations as possible. In just 45 days, the team helped create more than 2,300 shelters across Nepal.

In the flurry of activity, Manandhar scarecely recalled the half-dozen graduate school applications she had started months before. Some of her letters of acceptance were due to arrive the very week of the quake. Without phone services, electricity or even mail, Manandhar did not realize she had been accepted to the UO until a week after the earthquake.

“I went to this place where they had internet. I checked my emails and I realized I got into University of Oregon and a bunch of other universities as well, but the time for telling them I would want to join them was already over,” she said. “I was already late. But with the University of Oregon, it was interesting because they knew about the earthquake. They kept sending me emails asking, ‘Are you fine? Is your family fine?’”

Manandhar’s leadership and talent caught the attention of recruiter Holly Coble at UO’s School of Architecture and Allied Arts. Despite intermittent email communication, she began working on a strategy to bring Manandhar to Oregon. The main challenge at the time was strictly financial.

News of the devastation in Nepal stirred a keen sense of regret for many in the UO community, as Eugene is a sister city to Kathmandu. Quickly, UO’s Office of International Affairs, in collaboration with the Office of Student Financial Aid and Scholarships, established a full tuition scholarship for students from Nepal. The scholarship’s main requirement: that the recipient would make the commitment to return home after graduation to support rebuilding efforts.

A search committee led by Abe Schafermeyer, director of UO’s International Student and Scholar Services, and Harvey Blustain, chairman of the Eugene-Kathmandu Sister City Association, selected Manandhar as the first recipient of the scholarship.

During her time at the UO, Manandhar has become an important cultural ambassador for the university, not only as the first Nepal Scholarship recipient but also as a member of the International Cultural Service Program, an international student group that connects students from around the world with community events and engagement opportunities.

Manandhar has also been working at the UO’s Energy Studies in Buildings Laboratory, led by professor Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg. As a graduate architecture student, she has been researching sustainable design, particularly passive heating and cooling methods in buildings.

After two years away, Manandhar will graduate from the UO this spring and plans to return home to finish what she started.

“One of the things people don’t understand is how impactful an event can be and the after effects of the earthquake. …I know it all happened two years ago, but my country is still in need,” Manandhar said. “I went back this winter to see what has happened, but the state is still the same. There are a lot of people who are still homeless. I sometimes feel guilty for having come here.”

But then Manandhar recalls a key conversation with her father, who urged her to come to Oregon, so one day she may return home and bring a new perspective that will help rebuild Nepal.

“I want to make a difference, even if it’s a little thing,” said Manandhar. “And that’s something I’ve always wanted to do.”