Music and art have long-shared a history of collaboration, from turn-of-the-century sheet music illustrations to the vibrant psychedelic album cover designs of the trippy ’60s and beyond.

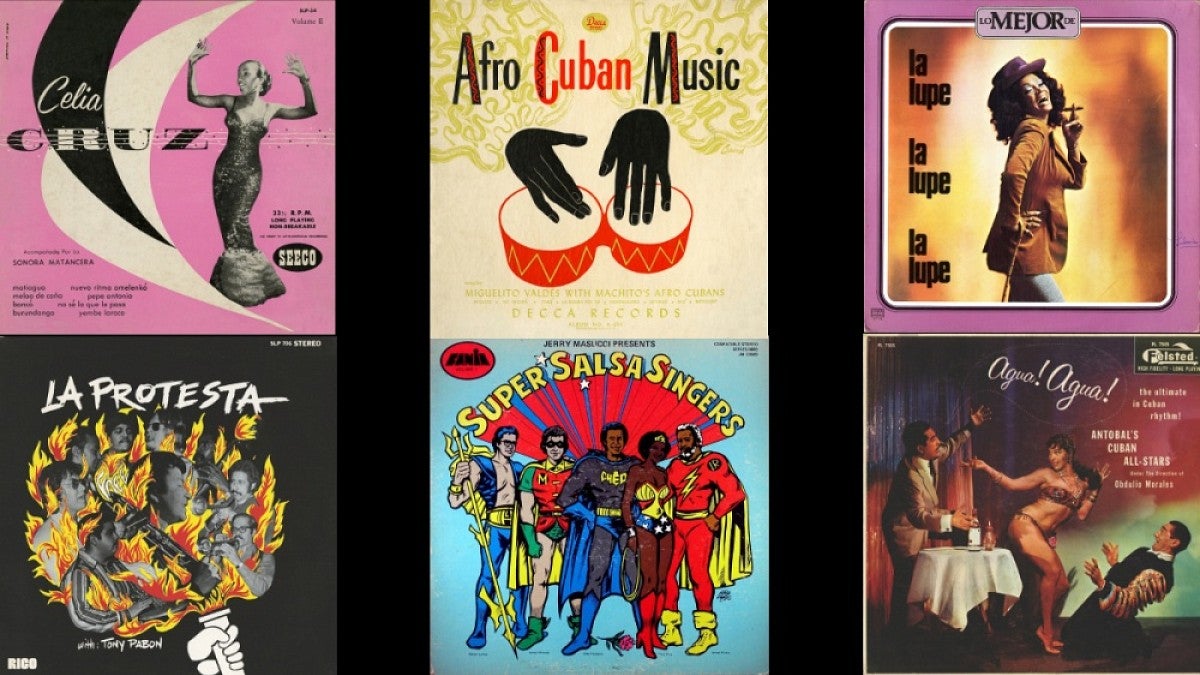

A slice of that history makes up the visual artistry of Latinx artists, who are the subject of an interactive exhibition at the UO’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art titled “Visual Clave: The Expression of the Latino/a Experience through Album Cover Art: 1940-90.” The installation features 40-50 original album covers that are, in some cases, paired with the original artwork that was created to produce the album cover.

The inspiration for the exhibit, and the culmination of more than a decade of research and collecting, is the 2005 book “Cocinando: 50 Years of Latin Album Cover Art” by Northampton, Massachusetts-based Cuban-American author, musician and artist Pablo Ygnasio. The result is a pared-down selection culled from a larger East Coast show that distills the essence of the Latinx experience in its many forms.

The co-curator of the exhibit is Phillip Scher, UO professor of anthropology and folklore and public culture and also divisional dean for social sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences. Scher has collaborated with Ygnasio on projects since their college days together and explained that although the work is certainly diverse, much of what was produced for the mass market in the early days was largely controlled by big music industry companies like RCA, Decca and Capitol Records.

“Record producers and record labels understood the popularity of popular music — there had been a big mambo craze — they understood that it sold records, but they were still largely controlling the recording marketing and distribution process,” Scher said. “The artists might have been contracted, who themselves may not have been from the (Latinx) community.”

That began to change, however, in the 1960s and ’70s as Latin American musicians and emergent independent record labels such as Fania began to hand over more control to the musicians as well as to the artists who designed the cover art.

That also meant taking control of the messaging.

Latinx artists not only used albums as an outlet to express themselves artistically but also oftentimes as a means of conveying provocative commentary on Hispanic topics of resistance or issues of a political, economic or cultural nature.

“You begin to see covers themselves reflecting more of what the musicians want to say about their music, their community, their relationship to the American experience,” Scher said. “There’s a variety of ways in which taking control of the process of production yields really different artwork.”

Indeed, the exhibition, which is grouped by themes, embraces everything from dance and food, “Spanglish”, lowriders and borders, and life in the barrio to protest, resistance and spirituality, to name a few. A section celebrating female artists provides imagery and context to those strong Latinas who persevered, despite pressure to “stay out of the macho world of salsa and ranchera” and to not speak to women’s issues and perspectives.

Likewise, a 1971 Izzy Sanabria album cover designed for the iconic Willie Colón record “La Gran Fuga/The Big Break”, also known as the “Wanted by the FBI,” features a mug shot of Colón and uses satire to break negative stereotypes of the “bad Latino.” That includes humorous quotes such as “armed with a trombone and considered dangerous” and “Occupation: singer, also a very dangerous man with his voice.” Ironically, Colón went on to a career in law enforcement.

Although it’s not featured in this grouping, Scher cited an example of subtle messaging in popular crossover musician Desi Arnaz’ album Babalú. It’s unlikely that the predominently Anglo-American audience tuning in to the 1950s era comedy sitcom “I Love Lucy” suspected that Arnaz’ signature, conga-infused song was a ceremonial drumming ritual designed to invoke the spirit of Babalú-Ayú.

“What he is essentially approximating there is an Afro-Cuban religious ceremony, in which the spirits are invoked by calling them out and drumming in certain patterns to have the spirits arrive, to come to the ritual and participate,” Scher explained. “And sometimes that participation meant essentially spirit possession. People were singing that and had no idea what they were singing about.”

Because the exhibition also embodies multiple disciplines — Latin American, international and ethnic studies, history, music, art, folklore, and anthropology — “the teaching potential is tremendous,” Scher said. As they view the artwork and peruse the program, museum visitors listen to piped-in Latin music selections drawn from each of the albums on display and can also take a turn at playing the claves, an important percussion instrument used in African, Brazilian and Cuban music.

Overall, Scher hopes that the takeaway for people is that they will think differently about pop cultural ephemera.

“For many people and for many ways, popular culture is a really viable way of communicating through artistic expression and reaching a lot of people, communicating the most pressing types of issues that confront a particular community,” he said.

Ygnasio and Scher will present a curator’s lecture, part of the CLLAS Spring 2019 Research Presentation Series, on April 11. The exhibition runs through April 21.

—By Sharleen Nelson, University Communications