The College of Education is mourning the passing of Siegfried “Zig” Engelmann, one of the most influential faculty members in its history.

Engelmann, who died Feb. 15 at age 87, led a team that invented a method of teaching called Direct Instruction. A celebration of life will be held at 1 p.m. April 13 at Venue 252, 252 Lawrence St., with a reception to follow.

Engelmann and his colleagues broke the process of teaching down into segments that required teachers to use precise language and sequences of examples when delivering lessons. One of its key elements was to teach students the foundation of a concept that later enabled them to more easily grasp higher-level ideas. Engelmann designed Direct Instruction to help even those with significant learning disabilities.

Carnine described Direct Instruction as having very much of an engineering approach, which was what enabled it to be so effective with disadvantaged children. When Engelmann saw students struggle to learn, he looked at the teacher and the method rather than the student as the source of the problem.

Carnine recalled some of Engelmann’s ideas that were revolutionary at the time but are now commonly accepted. In the 1960s, Engelmann worked with a graduate student to show Down syndrome children could be taught to read. He published a study showing that it was possible to raise the IQs of disadvantaged children. He also debunked myths about race and learning capabilities.

“The reach of what he’s done is so remarkable,” Carnine said.

Engelmann came to the field via a distinctly untraditional route. He earned a bachelor’s in philosophy from the University of Illinois and ended up working for an advertising firm. Television was just beginning to become widespread, and a client who owned a candy company wanted to know how many times children needed to hear a jingle before they’d remember it.

Engelmann contacted a number of colleges and universities and discovered that none had the answer. So he decided to figure it out himself.

“As he was working with those kids, he realized what his path in life was,” said his son Owen, who now serves as director of curricular resources at the National Institute for Direct Instruction, the firm Engelmann and others launched roughly 20 years ago.

That nontraditional background let Engelmann look at the process of teaching as going forward from the basics.

Engelmann joined the UO faculty in 1970. He eventually wrote more than 100 programs covering academic subjects from preschool to high school along and others. Teachers trained in Direct Instruction taught millions of at-risk children, often when nothing else worked.

Owen Engelmann said his father had a single-minded focus on improving teaching. He was brilliant and efficient but that didn’t mean he worked less and played more. He would regularly log 72- to 100-hour work weeks. Only in the past five years did he work 40 hours.

“The day before he died he was in a hospital bed in his living room,” Owen Engelmann said. “He looked at me and said, ‘Why am I here? Let’s get to the office. I should be at work.’”

Rob Horner was one of those who worked closely with Zig Engelmann over the years. Horner first met him when he was working toward his doctorate and later joined him on the College of Education faculty.

“Zig’s contribution, the idea of Direct Instruction, was how do you take knowledge and make it accessible,” Horner said.

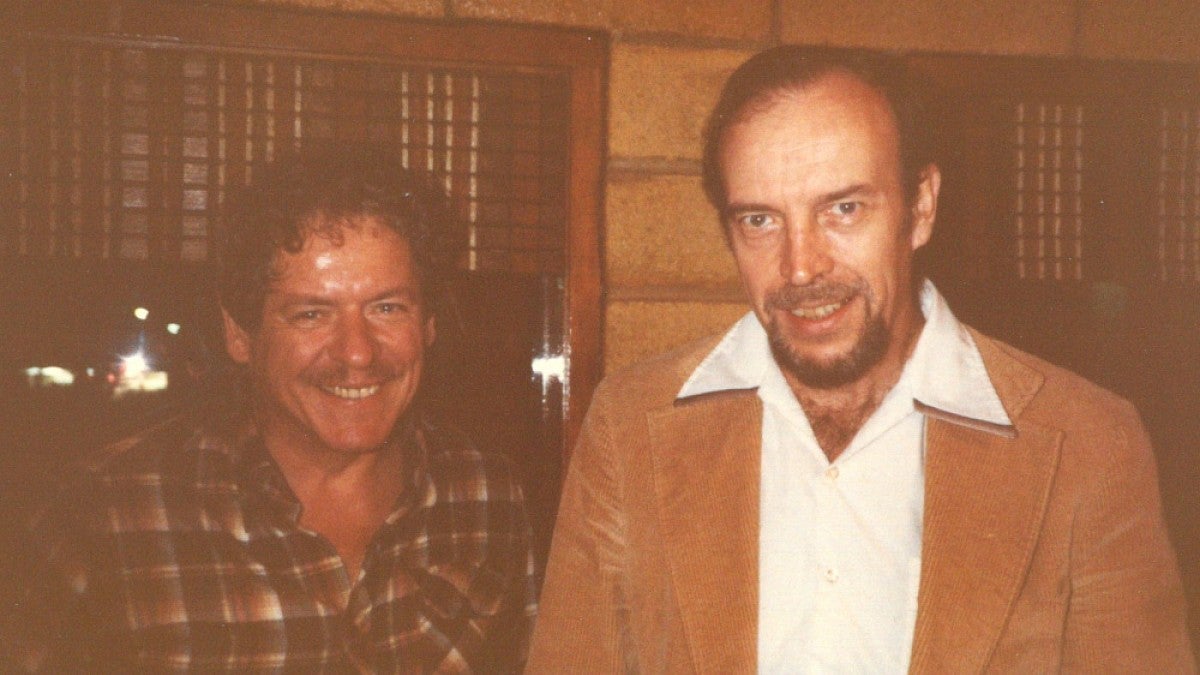

Geoff Colvin remembers attending a conference in Eugene during the summer of 1977 where Engelmann was presenting. Colvin connected immediately with the man and his ideas.

“Anything you call learning he had a profound impact on,” added Colvin, a former College of Education faculty member and one of Engelmann's closest and longest colleagues. “He made a system out of learning.”

Colvin said the way District Instruction was designed allowed it to be transferrable to teaching everything from math and English to athletic skills for sports, and how to build on previous knowledge. He knew what skills would be required later on and how to build up to them.

“Zig had these three big goals,” Horner said. “One: define the rules by which knowledge is transmitted to all. Two: take those rules and demonstrate you can build programs people can use, and three, implement that approach at a scale that changes the world. Zig did the first two. He’s going to expect us to gear up and get the third done.”

—By Jim Murez, University Communications