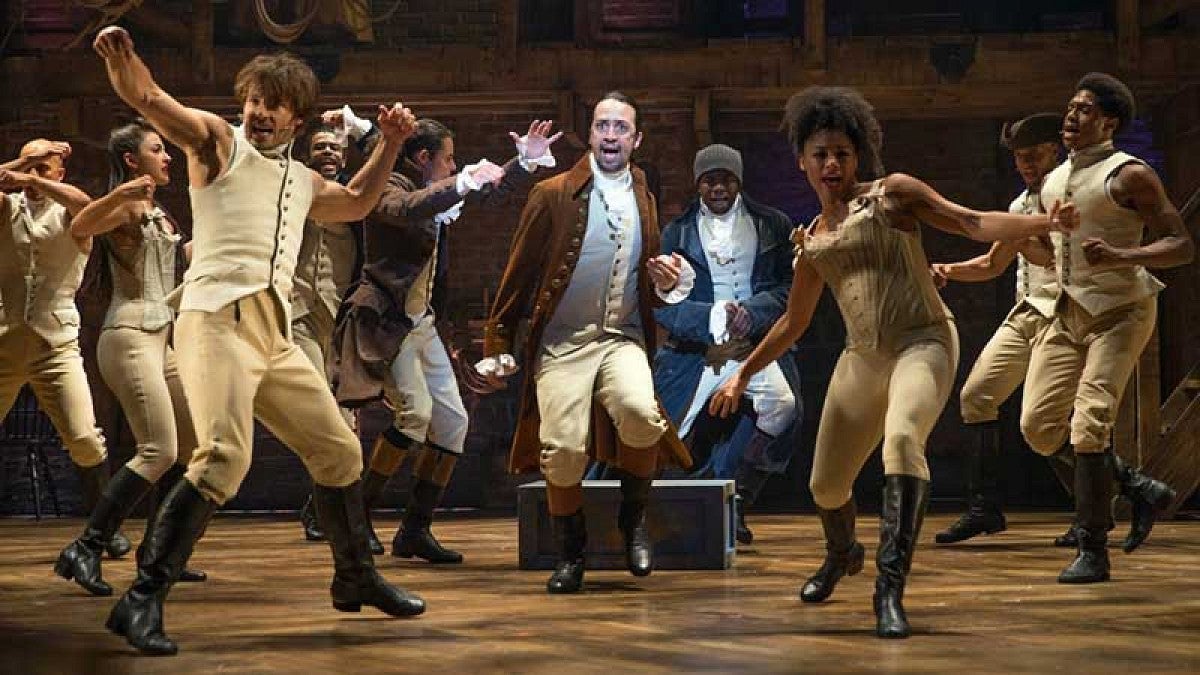

When Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop musical masterpiece “Hamilton” debuted on Broadway in 2015, it was described as “lightning in a bottle,” but many wondered if a streamed film version in 2020 could recapture that spark.

Considering that since its July 3 release, coinciding with America’s 244th birthday, “Hamilton” was the most-viewed single title across any streaming platform in early July, breaking streaming records for Disney+, the answer is a resounding yes.

From its racially diverse cast to a score that blends hip-hop, jazz, R&B and rap, the Tony Award-winning musical chronicles the Revolution-era life and death of Alexander Hamilton, who served under George Washington as the United States’ first secretary of the treasury.

With plans to introduce the popular theatrical show to a wider audience, one of the final live shows featuring the original cast was filmed in 2016 for an October 2020 theater release. But when the pandemic hit, shuttering cinemas, the Disney+ streaming service purchased the rights.

UO theater arts senior instructor Janet Rose streamed the recording during a Zoom watch party with a group of stage managers.

“The recorded version is wonderful,” she said. “Wonderful melodies and so many memorable lyrics, even from a first listening. If it had been an original cast recording from my college years I would have worn down the grooves.”

Limited runs and high-priced tickets kept many people from seeing the Broadway production, but Professor Emerita Alexandra Bonds saw “Hamilton” live onstage in London.

“What a wonderful gift to provide this access to everyone,” she said. “Though the immediacy of the actor/audience relationship can’t be reproduced in film, it is thrilling to be able to see stage performances that one would never be able to attend in person.”

Rose was also impressed with the camera work, which gave viewers at home a chance to experience live theater as though they were a part of the audience.

“As a lighting designer, I’m usually disappointed with recorded stage plays,” she said. “But the technology and definition are now advanced enough we can see the actual colors, contrasts and patterns the designer created. Yes, there are edits to closeups, but the visual framework is usually wide enough to appreciate the entire composition, as you would in the theater.”

And the best part, according to Rose: “In July 2020 everyone is talking about a piece of theater.”

It’s good theater, but is it good history?

Despite a cast mostly comprised of people of color and a fabulous rap score that has audiences singing along, some say Hamilton merely skims the surface of race and slavery.

Against the backdrop of a global pandemic, a polarized nation and the brutal murder of George Floyd and others at the hands of police that sparked protests in cities across the country, the nation is in a much different place in 2020 than in 2015 when “Hamilton” originally debuted.

“It would be quite different if it was written today,” said Department of History head and associate professor Brett Rushforth. “We are at a moment when we’re having a real discussion, a hard discussion, about Black Lives Matter, about systemic racism, in a way we weren’t five years ago.”

He cites a Harvard Gazette article written by Pulitzer Prize-winner Annette Gordon-Reed, who visited the UO in April 2017. She points out that aside from failing to mention that most of the Founding Fathers were slave owners in real life, Hamilton himself was an abolitionist, but he bought and sold slaves for his in-laws. Opposing slavery was never at the forefront of his agenda, Rushforth said, and he was very much an elitist and he was in favor of having a president for life.

About 10 years ago, Rushforth noted, a huge controversy erupted over a Hamilton exhibition at the New York Public Library.

“Progressive historians were saying we shouldn’t celebrate this guy,” he said. “He is anti-democratic. He is an uber-capitalist. He is the symbol of the greedy Wall Street that’s taking from Main Street. But then ‘Hamilton’ came out and everybody started singing along. And he looks very different.”

Still, he concedes that despite the historical flaws, now more than ever, people of color need to see representation onscreen.

“The benefit of it coming out right now is that you have the most popular thing that was watched over the Fourth of July weekend featuring almost entirely a Black cast and powerful performances by men and women of color,” Rushforth said. “Just to have that be front and center suggests that we have conversations that are taking this seriously but also that we have representation.”

He believes getting people interested in history and changing people’s preconceived notions was always Lin-Manual Miranda’s intent.

“He wanted to de-censor the white narrative, de-censor the presumption that certain people that look a certain way are who we think of as leaders,” Rushforth said. “It was never meant to be just a play. It’s a conversation starter.”

Indeed, the songs in “Hamilton” are a common point for discussion in Rushforth’s history classes.

“We talk about what is represented, what isn’t represented,” he said. “What’s left in and what’s left out? How do we choose what story to tell? It certainly provides an opportunity, an entry point for us to do that.”

Ultimately, whether Hamilton will be a force for good depends on what people choose to do with it.

“Art itself isn’t going to do the work,” Rushforth said. “Just by itself, it’s entertaining and it can be moving but it’s not likely to have the kind of transformative affect that we might hope if we just try to let it do its own work. As educators, as consumers, as parents, we have to choose to take this expression and engage it in ways that actually can turn it to good.”

—By Sharleen Nelson, University Communications