An online parenting skills program developed at the University of Oregon can help parents in rural areas who struggle with substance use or mental health and may have limited access to community resources.

Parents who engaged with the program, known as the Family Check-Up, via their smartphones reported fewer symptoms of depression and improved parenting effectiveness compared with a group of parents who did not participate in the program, a new study shows.

The paper recently appeared in the journal Early Childhood Research Quarterly. It was authored by Kate Hails, a research associate with the UO Prevention Science Institute, and several institute collaborators.

The Family Check-Up is backed by almost 30 years of research. The original version is delivered in-person, often at schools or community health centers. The online version, delivered via a web app that complies with federal health privacy laws, can greatly broaden the program’s reach.

The new research shows the online version’s potential for helping parents, particularly those living in rural areas, which have been disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic. Compared to their more urban counterparts, those parents may lack access to community resources or might resist getting help because they can’t do so anonymously, Hails said.

“Our goal was to reduce as many barriers as possible to parents receiving this kind of support,” she said.

Parents in the study received services at home using a smartphone, which many families already have. The research focused on parents of children 1½ to 5 years old. A third of parents in the study reported past opioid misuse or symptoms of depression and anxiety, and 4 out of 10 families lived in rural communities.

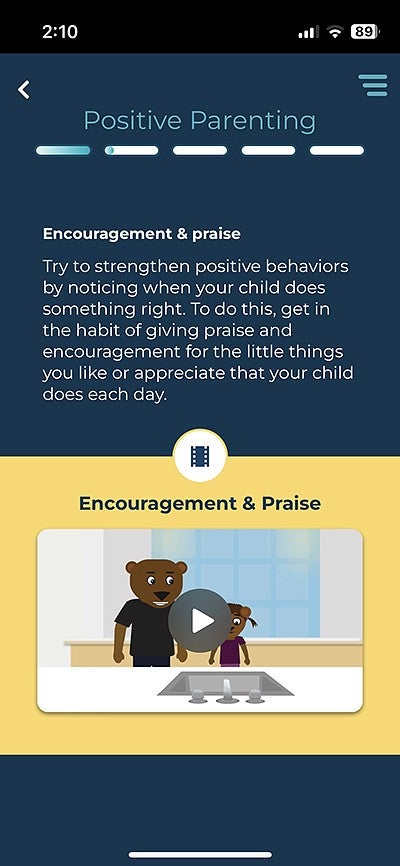

Parents in the study completed an average of 1½ hours of the program over three months, watching video content on their phones, usually in short snippets of 5 to 10 minutes. The videos featured an animated bear family and covered parenting skills such as quality time, positive reinforcement, and setting consistent limits and boundaries with young children.

Over the three months, parents also spoke on the phone five or six times with a family coach, who was a trained mental health provider. Each conversation lasted about 20 minutes.

In addition to writing the paper, Hails was one of the family coaches.

“Parents shared with me that they liked getting the training on their smartphone where they could access it more easily in small bits and pieces wherever they were — while they were nursing their infant or waiting in line at the grocery store, for example — because parents reported feeling stressed and having trouble finding time to engage with the training,” Hails said.

According to one parent: “The app was easy to use and because it was on my phone, I could do it while nursing or holding my baby. I found it a good alternative to being on social media (it felt more rewarding too than social media).”

Mental health issues, substance misuse or both affect many families in the United States, underscoring the critical need for accessible and effective parenting support, the researchers said.

In the U.S., 1 in 5 parents of children younger than 18 experienced mental illness in the prior year, and 1 in 8 children lives with a parent with a substance use disorder, according to 2017 data, which is the most recent available. The rate of children being removed from their homes because of their parents' substance use has risen dramatically since 2012, the paper noted.

Past studies have found that responsive parenting and good relationships between parents and young children are linked to children’s cognitive, social and emotional development. Parents with behavioral health challenges are at greater risk of parenting challenges and stress, which can harm their children’s development, studies found.

Hails collaborated on the paper with Anna Cecilia McWhirter, Audrey Sileci and Beth Stormshak, all researchers with the UO Prevention Science Institute, which operates out of UO campuses in Eugene and Portland.

The study is the latest research on the Family Check-Up, which Stormshak and other researchers have evaluated and developed over almost 30 years.

Previous studies involving infants through adolescents show the Family Check-Up is associated with a range of positive outcomes, from gains in parenting skills, improved parent mental health and well-being, and reduced child behavioral and emotional problems.

A few years ago, Stormshak launched a company, Northwest Prevention Science, to provide training and implementation for the Family Check-Up.

Future study on delivering the Family Check-Up to families in rural areas will focus on implementation strategies, Hails said. Could staff at community agencies — a day care, for instance — be trained to sign up parents for the program and help guide and motivate them to engage with it? Could parents effectively use the program on their own, without a coach? How much interaction is required for parents to get the greatest benefit from the program?

The researchers want to get the skills training to as many parents as possible, enabling parents to identify their strengths and challenges and make improvements that will benefit themselves and their children.

“The most valuable part of this experience was the positive focus on parenting,” one of the study’s parent participants reported. “It felt supportive in a way that helped me have confidence to make changes.”

—By Sherri Buri McDonald, University Communications

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Family Check-Up is a registered trademark of the University of Oregon.