Helen Neville, a leading voice for brain research at the University of Oregon since her arrival on campus in 1995, died Friday, Oct. 12, after a long illness. She was 72.

The Canadian-born Neville was known internationally for her work on early brain development and for moving her findings into practical applications, with a special focus on fostering neurocognitive development in children from adverse backgrounds.

“Helen was one of the most influential and visionary psychologists and neuroscientists of her time,” said Ulrich Mayr, head of the Department of Psychology. “She has done groundbreaking work on the neural basis of language; the plasticity of sensory, attentional and language systems; and most recently on how to leverage her insights in order to attack negative effects of poverty on the brain. Our thoughts are with Helen’s close family and relatives.”

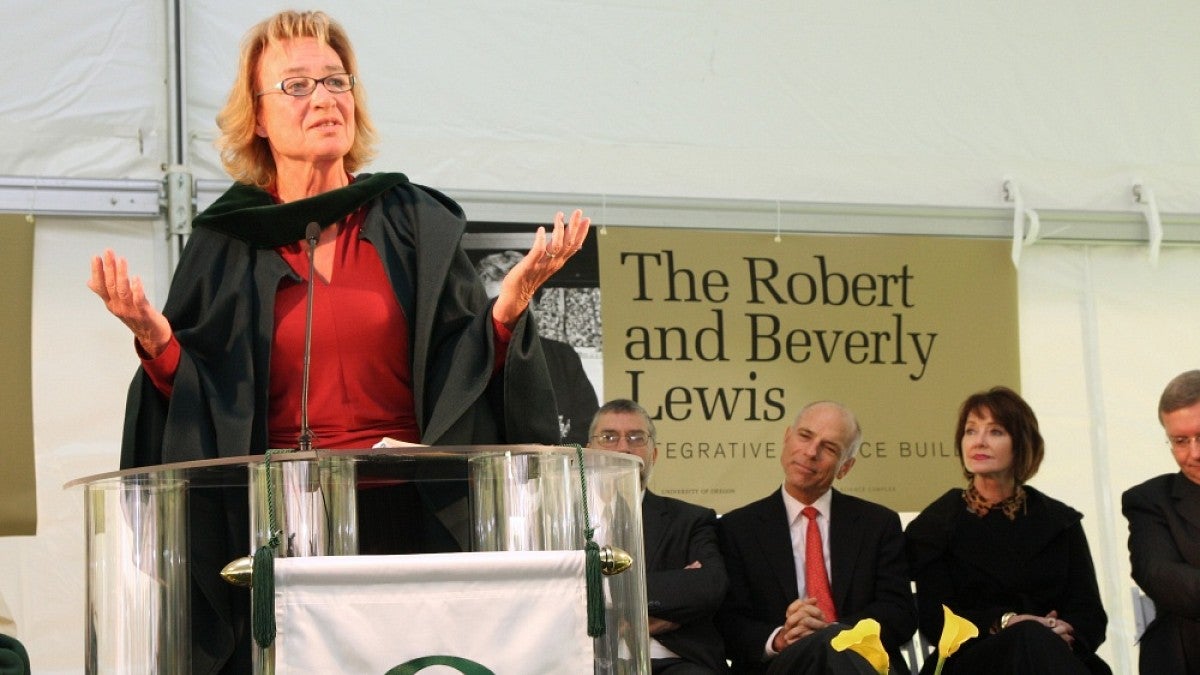

Neville held the Robert and Beverly Lewis Chair in Neuroscience from Sept. 16, 2002, until June 30, 2016. She also was the founder and longtime director the UO’s Brain Development Lab.

Neville played a key role in advocating for the acquisition of the UO’s first magnetic resonance imaging scanner, an effort that led to the founding in 2001 of the Robert and Beverly Lewis Center for Neuroimaging. Her voice also was vital in the construction of the Lewis Integrative Science Building, which opened in 2012. Both facilities became realities through generous financial support from UO alumni Beverly Deichler Lewis and Robert Bronson Lewis.

Neville used psychophysical, electrophysiological and magnetic resonance imaging techniques to study the development and plasticity of the human brain. She was an influential mentor for several generations of doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers, many of whom have gone on to make important contributions in their own right, Mayr said.

Neville, while a graduate student at Cornell University, made a solid first impression on the UO’s Michael Posner. They met when Posner – invited by his brother, a brain cancer researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering – joined a group gathering that included Neville and her Cornell mentor Eric Lennenberg. They told Posner about a program that was making strong connections between psychology and brain research.

“Hearing this was exciting. This was, for me, a remote goal,” recalled Posner, now a professor emeritus of psychology and a National Medal of Science winner. “I was studying how fast people responded to certain stimuli and was still some years from being able to connect those studies to neural mechanisms.”

Before Neville arrived at the UO, Posner said, she had learned to penetrate the brain’s electrical activity and begin making connections with language processing while working with researchers at the Salk Institute and University of California, San Diego.

“It was very exciting when she agreed to accept a position at Oregon,” Posner said. “That decision led to many important advantages for all us. Her many discoveries and public service brought a lot to our program.”

Christina Karns, director of the Emotions and Neuroplasticity Project in the Department of Psychology, described Neville “as a rare blend of scientist and communicator.” As a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, she attended a presentation by Neville.

“Helen gave a spellbinding talk,” Karns said. “I had never seen anything like it. Not only did she convey crisp neuroplasticity research with finesse, she shared pictures of the mobile brain lab – a converted RV – that was used to collect EEG data in hard-to-reach communities. When I joined her lab as a postdoc, I continued to be in awe of the span of her vision. It seemed like anything was possible for Helen.”

Neville's extensive public outreach included public and academic talks around the world. In 2009, her lab created a 12-segment DVD "Changing Brains: Effects of Experience on Human Development" for use by parents, teachers, caregivers, policymakers and anyone else interested in the mysteries of the brain.

In 2013, Neville received the William James Fellow Award from the Association for Psychological Science in recognition of her lifetime influence on research in the field of psychology. James, who died in 1910, is considered the father of American psychology.

The UO’s Marjorie Taylor, a professor emeritus, nominated Neville for the William James award, noting that Neville’s findings had profound implications for the basic scientific understanding of cognition, perception and language. She specifically pointed to Neville’s work with deaf students.

“Her research has demonstrated that deaf subjects show enhanced performance in the visual processing of peripheral space and motion,” Taylor wrote in her nomination letter. “By using a control group of hearing individuals who were raised with American Sign Language, she found that improved visual attention in the deaf is the result of deprivation.”

Taylor added that Neville’s efforts helped to identify the mechanisms involved in how the brain compensates for both deafness and blindness.

“Her dedication and passion as an educator cannot be fully understood in terms of university courses,” Taylor also wrote. “Helen teaches everyone. She regularly goes to local public schools and gives children a human brain to hold in their own hands. She lectures locally to lay audiences, travels the world to give scientific presentations, and is a regular instructor at summer institutes in cognitive neuroscience.”

In 2014, Neville was chosen as a foreign associate of the National Academy of Sciences in recognition of distinguished and continuing achievements in original research. In 2007, she was elected into American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Neville earned a bachelor's degree from the University of British Columbia, a master's degree from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and a doctorate from Cornell University.

—By Jim Barlow, University Communications