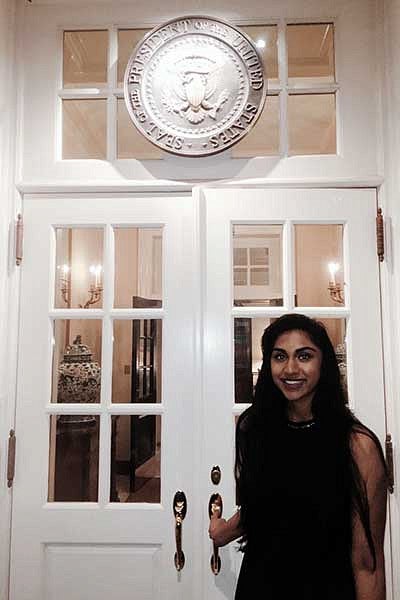

Manju Bangalore’s favorite memory stays with her in sharp, crisp detail.

“I was really young, like five or six, and my dad would pick me up from school, and we would take the back roads home,” she says as she laughs. “And as we got closer to the railroad tracks, he’d say in a pilot’s voice, ‘Air traffic control, this is WCH 741’—that was his license plate—‘Co-pilot and I are ready for takeoff. Are we cleared?’ Then he would speed up right at the tracks and for a moment, just a millisecond, we’d be up in the air, and that stomach feeling made me so excited. I was flying. I was in the air.”

Although her father was just playing a game, those moments in the air—the ability to fly—stayed with Bangalore and has influenced every decision she’s made since.

She is determined to accomplish the height of flight: Bangalore wants to become an astronaut before she’s 30.

Leaving the Earth

Bangalore’s first NASA internship in 2015 at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, “focused on the economics of in-space propulsion,” she says as simply as if she’s describing a summer job serving frozen yogurt. “All rockets require chemical propulsion to leave the Earth—they’re the only systems strong enough to escape Earth’s gravity—but once you get into space, you have the ability to choose other options, like electric. My project looked at the economic benefits and disadvantages of choosing electric propulsion over chemical.”

“I know I had the opportunity to work at really cool places,” she acknowledges. “But I applied to ... two or three dozen is a conservative estimate of how many internships I applied to.”

That fact—that she secured several amazing internships but didn’t get others—is important to Bangalore. Achievement, clearly, is something that is worked for, not something delivered.

“I’ve gotten a lot of rejection letters, so you can succeed and fail at the same time, right?” she questions. “I can get an acceptance at one place and also fail at 40 other things, too. I am happy to show you a picture of all of them!”

“I’m proud to say I failed the entire year.”

It’s also vital to Bangalore, a first generation Indian-American, who she says, didn’t know what the SATs were in high school or where to take them, to recognize that as a woman of color, especially one in the sciences, she is not expected to attain such coveted positions.

“Women in the sciences or people of color in the sciences are just marginalized communities who are told that failure is really prevalent for them,” she says. “When people have really low expectations of a woman or a person of color in the sciences, it’s easy to surprise them but it makes it even more worth it to surprise them.”

In front of the spectacular telescope in his office in Willamette Hall, Fisher says four words that describe Bangalore: Extremely energetic. Personable. Organized.

“She’s one of our most dedicated students in the physics major,” Fisher says. “She’s very intellectually capable; a very, very smart woman. She’s trying to go and grab physics by the shoulders shake it and get everything she can out of it.”

It was Fisher that guided her through the application process for the many, many internships she applied for, and Bangalore credits him with encouraging her to try for what seemed like the impossible.

“I spent my sophomore year on campus in a lab, and I’m proud to say I failed the entire year,” Bangalore admits. “I felt terrible because you’re supposed to make some progress in that time, but that is the very nature of science; you fail constantly, and you know as much as it sucks, you just have to be able to get back up. It’s a lot easier to get back up when you have people like Fisher helping you. He’s also a big reason why I chose science literacy as my platform in the Miss Oregon USA pageant.”

Yes, it’s real.

And it’s real.

Bangalore saw the local pageant as an opportunity to spread the word about science to children and students in a way that they could understand the magic of physics like she did when her father started flying over railroad tracks in their family car. To make it simple but exciting. To explain science in ways that makes it accessible and reachable. After an interview process, she won the county pageant, and this month, she’ll travel to Portland to compete for the Miss Oregon USA title. It’s something she takes seriously, counting every piece of lettuce she puts in her mouth, in every repetition her trainer encourages her to make to increase her upper body strength. She wants to win this. She wants to do it for science.

In her family’s living room in Corvallis, Bangalore plays with her tiny dog, Murphy, as her parents, Phani and Geetha, sit in their kitchen sipping steaming chai tea that Geetha has brewed from a collection of spices. Newly arrived in the United States in the 1960s, Phani started a seed research company with $500, and when his bride, Geetha, arrived stateside through an arranged marriage, she gave up her career as a lawyer practicing in the highest court in the state of Karnataka in India to work with the business, which they have built into a successful, reputable research company.

“She Wants to Be Everything.”

“She was about two and a half years old and we had taken her to Sun River for a seed convention,” Geetha says. “There was a thousand people there, dancers were on the stage, it was a family event. This little girl—” she points to Manju, “she ran to the stage, I couldn’t even catch her, and she started dancing. She got a standing ovation. From the beginning, she had so much energy. She wants to be everything.”

Manju bursts out laughing and rolls her eyes. “Mom,” she says

It was Geetha that took Manju back to India nearly every year to spend her summers working at the same orphanage in Bengaluru. Over time, Manju grew up with the kids she spent her summers with, got to know them; they became playmates, friends.

“Many of those children became doctors and lawyers,” Geetha adds.

It was that foundation in giving back, the duty of serving the community that inspired Bangalore to establish Rosie, a nonprofit organization started in 2015 that supplies more than a dozen outlets, including homeless and family shelters, Planned Parenthood of SW Oregon, Womenspace and the Oregon State University Food pantry with menstrual supplies and educational services. Last year, Rosie began servicing Balavikasita Orphanage in India, providing the girls there with menstrual supplies, education, nutritional supplements, and medical access.

At a team meeting on a Sunday night in May on the fourth floor of the Knight Library, a gala is being planned for this fall. Bangalore is making sure everyone knows their roles: What type of appetizers should they have, who is responsible for linens, what type of entertainment should they look for?

“Jugglers? Contortionists with those silk panels?” someone suggests.

“Fire jugglers would be awesome,” someone else says, and the group laughs.

But it’s not all laughter and whimsy in the meeting tonight; Bangalore is transitioning out of her role as executive director to a more informal role of a mentor. The deputy director is graduating, so most of the leadership team is leaving. Bangalore feels confident she is leaving the nonprofit in good hands; they are a tight group, and she’ll be departing to Houston in a month for her second internship at NASA.

Higher Ground

When the water started seeping under the door, Bangalore was worried, but not much. Her apartment was in an elevated portion of Houston while Hurricane Harvey had been pummeling the town already for a day. She still felt safe, even with the inch of water that was spreading itself around her home.

Within minutes, the inch became two, became three. Bangalore called 911, but no one came; after a while, with the water still invading, she called again.

When the water reached her knees, she grabbed her car keys to leave and head to the higher ground of a friend’s house that was close by; a three-minute drive. Once outside, she realized that the car she had shipped from Eugene was inoperable; water was far above the doors. It took less than a second for her to decide to walk in the thigh-high water. Her shoes were snatched by the current instantly, and for two miles after she found drier ground near a highway, she walked barefoot until she was spotted by a police car that took her to safety at her friend’s house, who happens to be Miss Mississippi USA, and who was also working at NASA.

“She let me have her car so I could get back and forth to NASA,” Bangalore says as she starts the engine. “Can you believe how nice that is?”

Her car is totaled, but she’ll get a new one when she returns to Corvallis before the fall term at UO begins. In January, she’ll be heading back to Houston with that new car, for her third internship at NASA.

It’s another step closer, another mark hit.

“People think it’s ridiculous to hope for it, they tell me that eight astronauts are chosen every two years out of fifteen thousand applicants—but they were chosen,” Bangalore says steadfastly. “The number is not zero. The probability is low, but if there’s a chance I can do something I will. I know at times I’m going to fail and I know it will be hard, but it’s so much better than not trying and wondering when I’m eighty why I didn’t apply for the astronaut corps.”

Become a Duck and Find Your Flock