Paleontologists at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History have reported the discovery of a land-dwelling dinosaur’s fossilized bone in Eastern Oregon — an exceedingly rare find in a state that was underwater throughout most of the dinosaur age.

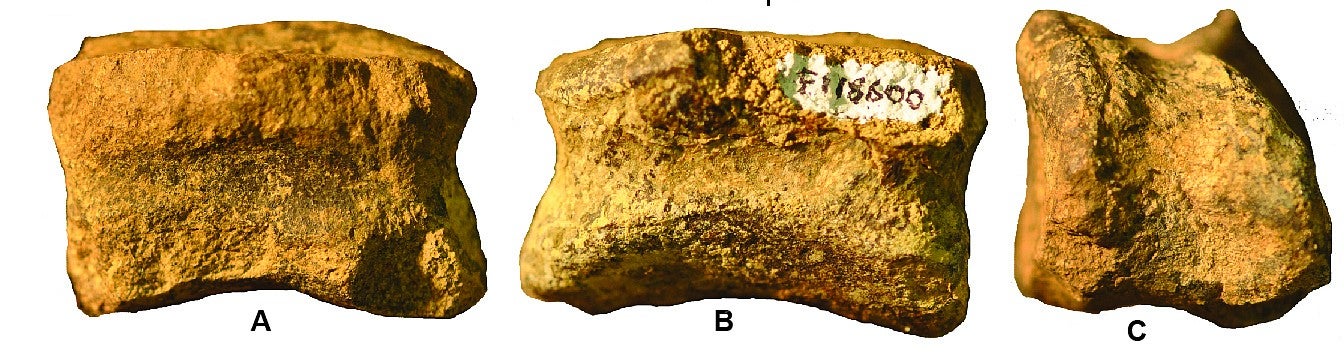

The toe bone belonged to a plant-eating, bipedal dinosaur known as an ornithopod and is estimated to date back 103 million years to the Cretaceous, a geological period that also gave rise to Tyrannosaurus rex.

Uncovered by UO earth sciences professor Greg Retallack during a 2015 field excursion near Mitchell, the find was published online in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology and is the first Oregon dinosaur fossil ever reported in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

“Oregon landscapes are rich with Cretaceous rocks, but they rarely contain the kinds of dinosaur remains we see elsewhere in the U.S.,” said Retallack, the museum’s director of fossil collections and the report’s lead author. “The rocks here are the right age but are mostly from under the sea where dinosaurs did not live or from swamps where dinosaur bones are seldom preserved.”

During the 2015 trip to Mitchell, part of a University of Oregon course on fossil plants, Retallack and his students surveyed a shale slope on Bureau of Land Management property. There he spotted the toe bone amid an array of mollusk fossils preserved in the marine rocks.

Edward Davis, a co-author on the report and the museum’s fossil collections manager, said the land-dweller’s bone likely ended up there after a posthumous stint in the ocean.

“It’s a phenomenon we sometimes call ‘bloat and float,’” he said. “That is, the animal died on shore in its terrestrial habitat, then washed out to sea, where it floated while bloated with decomposition gasses. Eventually it burst, and only this toe bone was entombed and became a fossil.”

Based on comparisons with other ornithopods, the co-authors estimate that the Mitchell dinosaur was more than 20 feet long and weighed nearly a ton.

“With such a small piece of the ornithopod, it’s hard to say much about its ecology,” said report co-author Samantha Hopkins, the museum’s curator of paleontology and an associate professor of earth sciences at the Clark Honors College. “However, just finding it in Oregon is exciting, because we rarely see evidence here of the dinosaurs we know must have been nearby.”

The report was also co-authored by the University of Calgary’s Jessica Theodor and UO doctoral student Paul Barrett.

Retallack said he doesn’t expect to find more dinosaur bones in Oregon marine rocks anytime soon.

“But we are now looking more carefully,” he said.

—By Kristin Strommer, Museum of Natural and Cultural History